Robot Soldiers Are Reporting For Duty

Unmanned ground vehicles are already playing a role in the Ukraine war

On December 23, 2025, the Ukrainian military announced that a robot from DevDroid, a domestic producer of combat robots, had held a position near Kharkiv for roughly 45 days against sporadic Russian attacks. Employed by the 3rd Separate Assault Brigade of the Ukrainian Armed Forces, this deployment is emblematic of how these robots are becoming more important in the grueling attritional warfare in Ukraine.

This particular event marks something of a milestone for ground robots, which are used by Ukraine for roles like reconnaissance, resupply, infantry support, and rescuing wounded personnel. Ukraine’s military is particularly focused on robotics deployment, with their goal being to deploy 15,000 unmanned ground vehicles (UGVs) — among them at the very least hundreds of DevDroid platforms — by the end of 2025.

This might seem strange to some: after all, aerial drones are the iconic face of robotic warfare. The DJI Mavic is particularly iconic; as one Russian military blogger recorded, “Mavic means death.” This sentiment — and the overwhelming superiority of Chinese dronemaker DJI — led the United States to implement a ban on the import of such systems from China. Ukraine’s Operation Spiderweb and Israel’s decapitating strikes on Iran during Operation Rising Lion would not have been possible without these transformative platforms.

But there are roles for which these smaller kamikaze platforms are not particularly suited: the war is currently a grinding attritional battle, with brutal trench fighting that has consumed hundreds of thousands of human lives already, leaving both sides scrambling for more personnel to fill the ranks. And, of course, reaching for technological solutions.

Why Ground Robots?

We can go on and on about the potential of small, disposable aerial drones in warfare (read my previous blog post, for example). These lightweight, low-cost machines are effective at eliminating enemy infantry and armor; they provide reconnaissance support; they mount ambushes. The Armed Forces of Ukraine received about three million first-person view (FPV) drones in 2025.

But these are not the only aims for warfare. In the end, war is about holding ground. Aerial drones may excel at engaging enemy forces, but arguably they’re just acting as a lightweight replacement for artillery. They can certainly engage the enemy; it’s been reported that drones cause 70% of casualties in Ukraine.

Note, however, that in World War II artillery and air strikes caused 50-70% of casualties. It’s not like the drone is replacing an infantryman. Inflicting casualties, largely, is not their job and has not been their job through much of history. Instead, as Napoleon Bonaparte said:

The hardest thing of all is to hold the ground you have taken.

This is where I think these ground drones come in, and why they have a very distinct role compared to the aerial variety (loitering munitions). Much of the Ukraine war is actually what appears to be almost old-fashioned trench warfare, with human soldiers digging in to hold territory against their enemies.

What These Robots Are Doing

It may surprise some users that we even want or need ground robots instead of just relying on swarms of drones, so let’s go into what these robots are actually doing a little bit more. There are two main classes of armed unmanned ground robots from DevDroid:

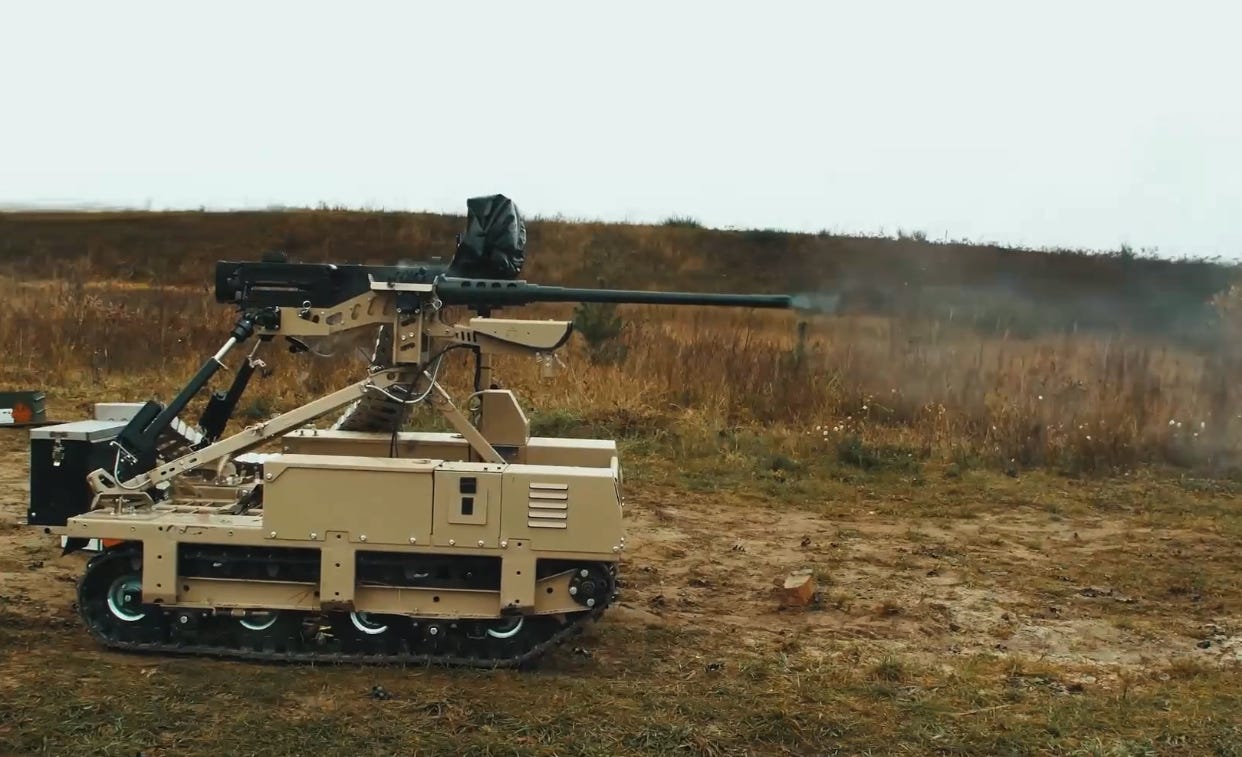

The machine-gun-armed TW 12.7, recently approved for use by the Ukrainian Ministry of Defense

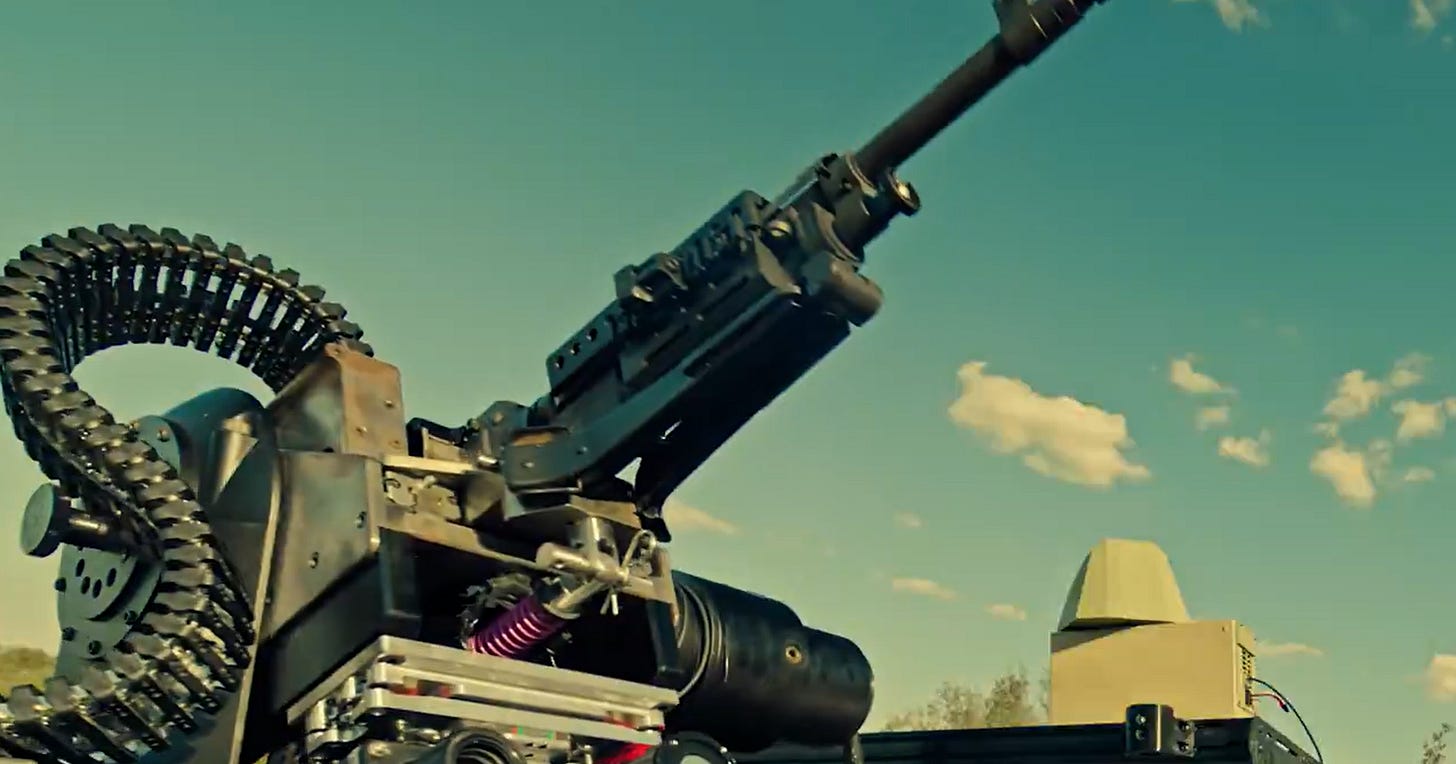

The NW 40, armed with a rapid-fire grenade launcher, used for ambushes against light armored vehicles and enemy convoys, and recently codified (officially inducted into service for state procurement)

In addition, we see many other types of ground robots — kamikaze ground robots, logistics/supply carriers, and others for evacuating the wounded. Many of these are useful for mounting ambushes or for protection against them (in particular using autonomous robots to resupply).

Probably the most important role these robots are serving is to keep soldiers out of line of fire. Robots like the Devdroid or the similar T-700 carry fairly heavy weapons. They can perform fire missions and suppressive fire, and conduct ambushes without exposing human soldiers the enemy. And a lot of what human infantry do, unfortunately, is dig in somewhere and get shot at.

When a robot is "holding a trench” for 45 days, it won’t have spent all of that time taking enemy fire — but it was important to that someone be there, at that intersection of trench lines, who could fire on approaching enemies and take fire in turn.

This process of trading fire creates friction between the two opposing forces, and most likely once the robot starts shooting, the enemy would fall back. If they actually wanted to take that position they might call for artillery or — yes— aerial drones. If no one was there to oppose them, they might just break through, and be able to interfere with supply lines or just seize ground, dig in, and call for reinforcements.

Both sides will start shooting well before any casualties are guaranteed or even likely, at least in any particular engagement. In the American War on Terror, US forces expended something like 250,000 rounds of ammunition for every insurgent killed. But the act of firing on a position — of putting vast amounts of lethal power downrange — forces soldiers into cover or retreat to avoid harm. It prevents movement, and locks down a whole area, even if the engagement between the two forces was very brief.

And this is why a bomb-armed quadrotor — or even 50 quadrotors — can’t do the same job. The gun-armed robots we see here can move around, take some measure of cover themselves, and are armored enough to be quite resistant to explosives and even the occasional suicide drone. They can threaten a very large area — engagement ranges for these weapons run from 50 to 800 meters — and prevent enemy movement through a large part of that area, for days or weeks at a time, all without endangering soldiers on their own side.

It’s a very different part of the puzzle that is a modern battlefield: as opposed to being disposable, high-precision “light artillery” like aerial drones, these robots are acting like infantry or “light tanks.”

Autonomy on the Horizon

As noted above, these robots are not autonomous. But this is likely to change, and it might not be very long before it does — and the reason comes back to aerial drones. Basically, today’s militaries badly need an economical solution to keeping the “lower skies” clear and their troops safe (or, at least, as safe as it gets in a warzone).

Currently, counter-drone efforts are largely a manual affair, using specially-equipped interceptors which, themselves, are human-piloted FPV drones. More autonomous and scalable solutions exist, but often interceptor missiles end up being more expensive than the robots they are shooting down!

This has led companies like Anduril and Allen Control Systems to start building autonomous gun platforms which can automatically detect, target, and shoot down fast moving drones. Think, similarly, to the Phalanx CIWS on American carriers: these shoot a lot of bullets (relatively cheap) to take out the incoming drone while protecting humans on their team.

There is, rightly, a lot of debate about robots making the decision to shoot against humans, and the United States Department of Defense still says humans will stay in the “kill chain” at all times. But if they’re just shooting down munitions, presumably, there is no issue.

Of course, as countermeasures (to remote operation of these robots) grow stronger, and artificial intelligence gets better, who’s to say that robots won’t start to be trusted with more and more autonomy when handed other targets?

Final Thoughts

The old cliche goes that necessity is the mother of invention. Many of these current combat robots exist to solve for very specific problems the Ukrainian military faces, particularly a lack of manpower.

But these still feel like they presage future warfare in important ways. These machines will appear first to help hold ground, and to secure the lower skies against enemy drones — but if the need arises, they’ll be doing more than that.

If you like this, or have any thoughts, please let me know below.

To learn more, read my previous article about aerial military drones below.

War Always Changes

Important changes have a way of happening slowly, then all at once. Nowhere is this more evident than in warfare.

Thanks for the piece. The framing of ground systems as ‘robot soldiers’ sets a nice tone, but I think that the roles of these different systems in the modern battlefield are more specific than artillery replacement/infantry replacement. Some are designed for support roles, some for point protection, some for different kinds of recon, some for target designation, etc. Battlefield needs are becoming more nuanced, and the systems to fill these needs are becoming more specialized. It is the same process that we see in general robotics.

Wonder why the T-700 Browning robot has two different machine guns. Range is a bit different, so I guess different targets, but seems a bit redundant.

Also, the ground drone holding something by itself for 45 days seems like a bit of a PR statement. I would think it would need resupply and arial drone cover at the least, and ideally other supporting troops if it was under fire. As you allude to, perhaps the Russians didn't want to take the position very badly. OTOH, I'm no military expert.