How do We Quantify Progress in Robotics?

Determining which robotics advances are real can be incredibly difficult

The release of the Imagenet dataset was a landmark moment for the nascent field of deep learning. This collection of what is now 14,197,122 images covering more than 100,000 concepts (“synonym sets” or synsets) was key in driving and assessing early progress in deep learning, in part because it signaled the ongoing shift from “better algorithms” to “better data,” which in turn unlocked much stronger algorithms. Quintessential, landmark deep learning papers like Resnet and ViT were evaluated on ImageNet.

The dataset has many nice qualities: compared to other popular vision datasets like CIFAR-100, ImageNet has much more variety; it has high-resolution images; a method working on ImageNet tells you something (not everything, but something!) about whether it will work in the real world. But it’s still manageable: most “Imagenet” results stem from Imagenet-1k, a clean subset of 1,000 chosen object classes (“Golden Retriever”, “Sofa”, et cetera).

But this was a very, very controlled problem: image classification; i.e. “which of these 100,000 classes does this image that I am looking at belong to?” Image classification is easy: the problem is clean, it’s well defined, it’s not going to change or fluctuate. It is, in short, it fails to characterize systems which operate via repeated interaction with their environment as opposed to a one-off image capture.

And so we come to robotics. With the rise of humanoid robots and massive funding for real-world robotics research, it’s more important than ever to be able to tell what actually works and what does not — but at the same time, this is more obfuscated than ever.

Fundamentally, though, there are two main options: evaluate in the real world (somehow!) or evaluate in a simulation. Each have serious advantages and disadvantages. Let’s talk about them.

If you’re interested in seeing more of this kind of post, please like and subscribe.

Why an Offline Dataset Doesn’t Make Sense

First, though, let’s discuss the issues with using an offline dataset for evaluating robot trajectories. It works for images and language, after all — why shouldn’t it work here?

An offline dataset might take the form: Predict action given current state observation and task description. However, robotics is an inherently interactive domain; small errors in action prediction accumulate over time, and lead to different outcomes. Good policies compensate for these, and recover from partial task failures.

Without an interactive environment to evaluate in, we can’t compute task success rates, and we can’t determine whether a policy would be useful at deployment time. This leaves us with two options: (1) test in an interactive simulation, and (2) find a way to compare methods on real hardware.

But Simulations are Getting Better

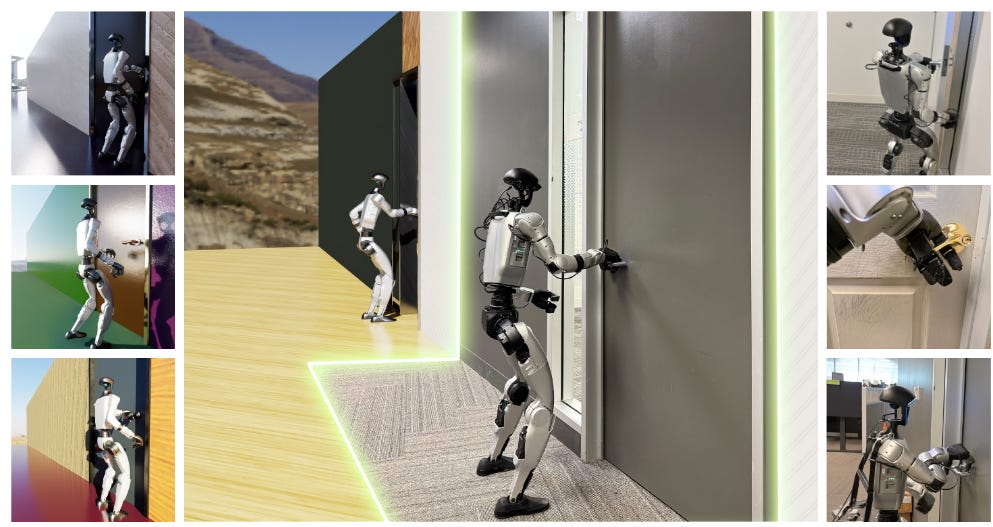

If we need interactivity, perhaps the best benchmark, then, will be in simulation. And simulations are getting more powerful, more interesting, and more diverse all the time. More importantly, we’re regularly seeing previously-impossible examples of sim-to-real transfer. See, for example, Doorman, by NVIDIA, which was sufficient to teach a robot to open a door — though note many difficulties involved in this work!

Simulations are getting more powerful and easier to use all the time. But few of these simulations rise to the level of a usable benchmark, i.e. something like Chatbot Arena, Humanity’s Last Exam, or SWE-Bench Verified.

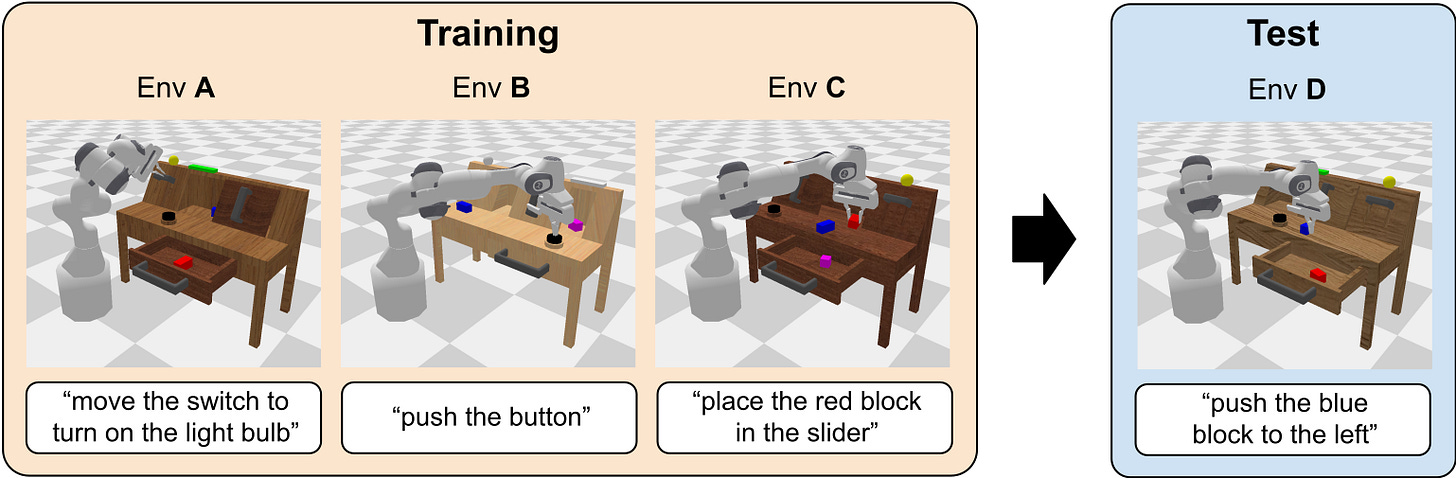

For robotics manipulation, two of the most notable benchmarks are Libero and Calvin. These implement a wide range of tasks with language conditioning (“push the button", “stack the blocks”), which means they can be used to train and evaluate multi-task policies. For mobile robotics tasks, the most notable simulation benchmark is Behavior 1k, which implements a thousand challenging simulated household tasks.

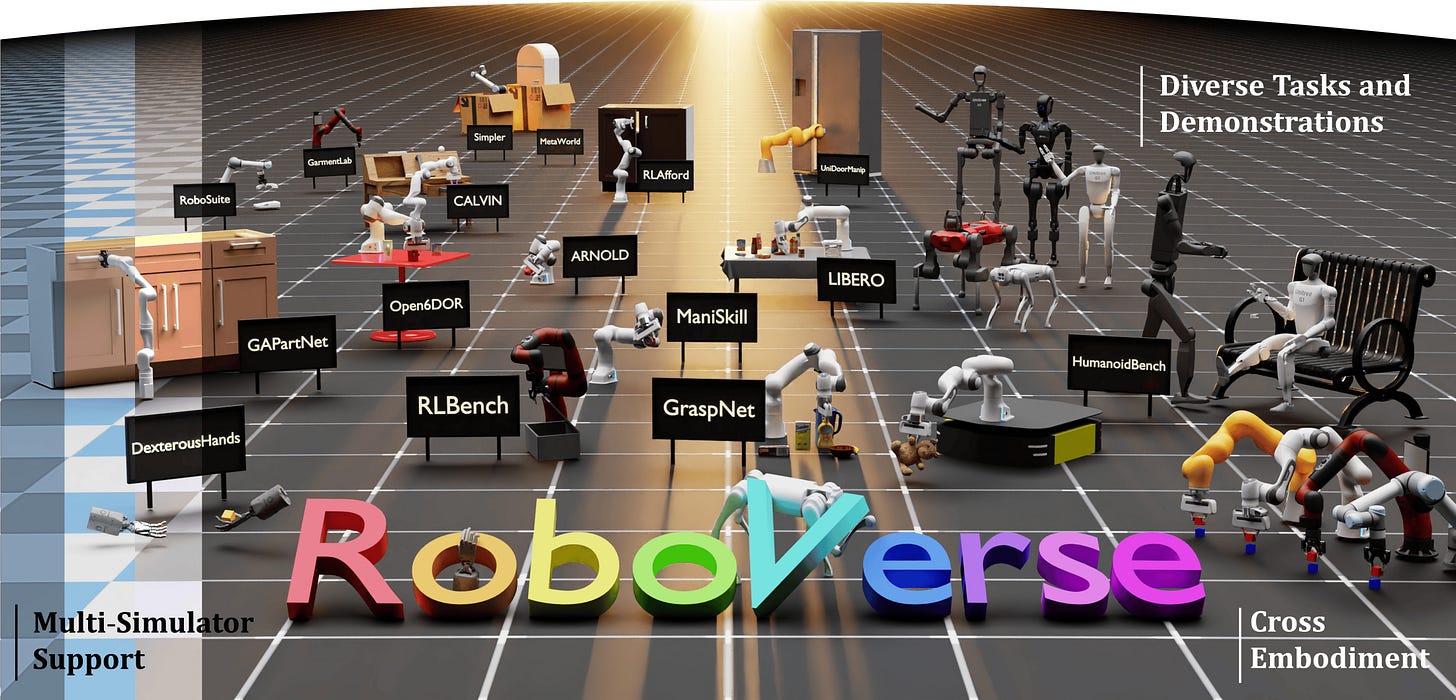

But there are many more, and they all have subtleties which impact which methods work. This makes it easy to “choose your own” subset of benchmarks upon which your model will perform the best, which renders moot the whole point of even having benchmarks in the first place! Efforts have been made to unify all of these different simulators, like Roboverse.

Another issue is that authoring tasks in simulation is hard. In the real world, if I want to have the robot stack blocks, I go buy some blocks and drop them in front of the robot. In a simulator, I need to get the friction parameters right, masses, make sure contact is working properly, et cetera. I need to implement cost functions (for RL) and success criteria, and this only gets harder as I start to scale simulation up. One notable effort to reduce this pain point is the Genesis simulator, which attempts to use user-prompted natural language to help create environments.

Fundamentally, though, simulations are still hard to work with and an inaccurate representation of the true robotics problem, without sensor and actuator noise, with overly-clean problems, and with unpredictable, often-inaccurate contact dynamics. As a result, there will always be a role for real-world evaluation.

Evaluating In the Real World

Obviously, comparing performance on a real-world task for robots is the benchmark. But running any kind of evaluation in the real world for robots is hard. In simulation, you don’t need to “reset the environment,” putting everything back where it was before you run again — something I have done many times in my life as a robotics researcher. Fortunately, we’ve seen a couple ways in which this problem might be addressed, especially inspired by recent work in large language models.

When the AI field moved towards large language models, we quickly saw a rapid proliferation in the number of benchmarks of ever-increasing difficulty - benchmarks like Humanity’s Last Exam fit the Imagenet mold of: here is a dataset, see if you can get the right answer.

But benchmarks quickly saturate; and they never solve the “real” repeated-interaction, high-dimensional data problem we actually care about, whether the goal is language or a robot. One evaluation method which exploded as a result was Chatbot Arena: a platform in which a user comes up with their own prompt, it is sent to two different LLMs, and the user chooses whichever response was better. While the particular implementation has not been without issues or critics (especially notable is Llama 4’s apparent benchmark-maxxing), the approach is scalable, in that it doesn’t require running a full sweep of all possible queries every time. While it’s not perfect, because no two evaluations are the same, it gives you an ELO rating which gives an idea how competitive every model is with other options out there.

This is a great fit for robotics, where similarly, running individual evaluations tend to be extremely expensive. Tournament-style evaluation most useful because it minimizes the number of expensive evaluations you need to run in order to see if it works; crowdsourcing queries also helps prevent overfitting to the benchmark (which was a perennial problem in a lot of computer vision research, and persists in many fields to this day).

Examples include RoboArena, which is a community-run cloud service for evaluating robot policies. Your policy gets executed on the cloud, and you just need to provide a service exposing it. This does limit the kinds of tasks that can be evaluated, though: latency will always be a serious issue.

The authors of the large humanoid robot dataset Humanoid Everyday are also planning a cloud service for evaluating robot policies on a real Unitree G1 humanoid; you can check their site for details (as of writing, it still says it’s coming soon) and watch our RoboPapers episode on Humanoid Everyday to learn more. You can also watch a podcast episode on RoboArena while you’re at it!

Common Real-World Platforms

All this is very limiting, though. Maybe we should just expect that people will just own robots upon which standard policies are expected to work, so that they can do their own evaluations on their own problems.

It might even be possible for something open source to take over, something that I’ve written about in the past. The HuggingFace SO-100 arms have seen some significant uptake in the hobbyist community, though very few have made their way into academic research papers that I’ve seen. We might see mobile versions of such a platform succeed; XLeRobot, for example allows for you to, at a fairly low cost, test out different mobile manipulation policies.

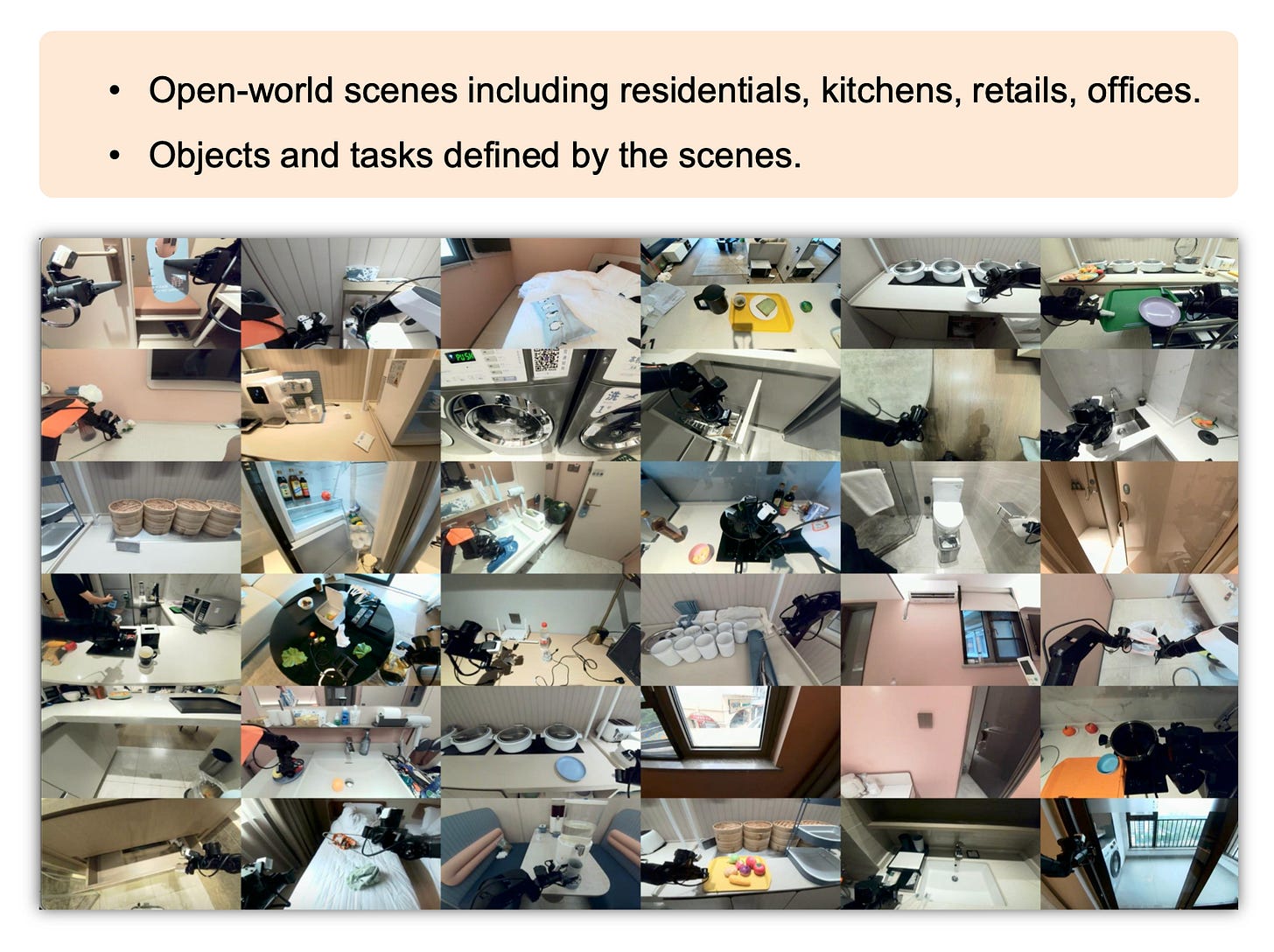

Of particular note today is the Galaxea R1. This platform is available for a relatively low cost, and comes in several varieties to support easy data collection, like the R1 Lite. The R1 Pro was used in the Stanford Behavior Challenge at Neurips 2025. You can download a VLA and associated pre-training data for it. It was even used in the recent RobbyAnt LingVLA, which used 20,000 hours of real-robot data.

The most common platforms right now are probably the Trossen ALOHA arms, the YAM arms from I2RT, and of course the Unitree G1. It’s notable how compared to previous systems — available even 2-3 years ago — all of these robots are spectacularly cheap. Robotics has become substantially more affordable, and robotics research more accessible. As a result, maybe the best way of telling which methods are “good” is just to watch to see which methods people build off of when performing experiments with these common platforms.

Final Thoughts

So let’s recap:

Offline datasets do not work because robots never do exactly the same thing, these errors compound, and all robot tasks are too multimodal for this to be meaningful

Simulations exist and are useful, but are niche, hard to implement, and often missing critical aspects of the real world (usually visual diversity, implementation of interesting/relevant tasks, and high-quality contact simulation)

Real-world evaluation is slow and horribly expensive to run, and can’t match the expectations of other AI fields like language or image understanding in terms of speed.

This sounds dire, and it actually gets somewhat worse; because all of this has focused on assessing algorithms, and robots are not merely algorithms: they’re hardware plus an algorithm. Hardware factors — joint positions, sensor placement, motor types, backlash, heat buildup, and more — often matter more to task execution than the algorithm you’re using.

So any “real” benchmark comparison of, say, Figure 03 vs. Tesla Optimus vs. 1x NEO would by necessity look more like a human competition, where participants, say, go to a test kitchen and see who can load a dishwasher the fastest.

We’ve seen the early evidence of such events, like the World Humanoid Games, or the many competitions we see every year at major robotics conferences like IROS and ICRA. These are likely to expand, although major companies right now have too much to lose and too little to gain to bother competing.

On the model side, the fact that you can just download and run pi-0.5 on your hardware, for example, is an incredibly promising start. In the end, though, the answer to the question, “how do we quantify progress in robotics?” has to be “all of the above.”

Excellent point on how error compounding makes offline datasets basically useles for robots. The lack of standardized benchmarks really does make it feel like we're all picking cherries to show off our best results. When I was testing manipulation policies the sim to real gap was always way bigger than any paper suggested especally with contact dynamics.

"authoring tasks in simulation is hard" This is such an excellent an easy-to-forget point. It's easy to underestimate how long it takes to make the simulation "work", whatever that even means.

I used to think that the DARPA challenges were helpful in quantifying and also seeding innovation - do you think that model makes sense?