Where the Horses Went

An optimistic case for robotics and what that means for the rest of us

When a technology finally clicks, the changes spread faster than anyone expects and have far more serious implications for society. I want to lay out a case here for robotics finally “clicking” within the next few years, and what that could look like for everyone. Technological change happens fast, and nowhere is that more obvious than in the early part of the 20th century.

There were 130,000 horses in New York City around 1900. By 1912, they were already outnumbered by automobiles; today, there are only 68 licensed carriages and probably a mere 200 horses in the entire city now. Despite peaking at 26 million, the United States population of horses went down to 3 million by 1960. As soon as the economic utility of the animals vanished, they disappeared from public life and the city changed forever essentially overnight.

In 1908, maybe 1% of American households had a car. This number tripled in the 1920s, going from 8 million to around 23 million. By 1948, half of all households had a car; by 1960, it was 75%. The shape of American cities changed completely over this window.

Predicting the future is very difficult, and the core problems in robotics are far from solved, but I think we’re seeing a very similar period of rapid change happening right now. The level of investment and growth in robotics and AI is reaching a fever pitch, well beyond what I expected 1-2 years ago. And, perhaps more importantly, most of what I have believed are substantial blockers to robotics deployments now seem solvable on a technical level:

Robots are relatively cheap, mass-produced, and of increasingly high quality, with a robust supply chain.

Data issues that have stymied robotics learning in the past look addressable.

Core learning technologies — both supervised training on large datasets and reinforcement learning in the real world — have been proven out.

All this means that we should see robots in a lot more industries and parts of society than we’ve ever seen in the past, so let’s talk about the future. But first, let’s lay out the case for robotics optimism — then we can get into what it means.

The big story of 2025, for me, is the sheer scale of production of humanoid robots. Companies like Agibot and UBTech are building humanoid robots by the thousands now, and sending them to work in factories belonging to the world’s biggest automakers — companies like BYD.

In general, the number of humanoid robotics companies, and teams working on humanoid robots, is skyrocketing. Most recently, Rivian announced that it is spinning off Mind Robotics, with $115 million in funding. Said founder and CEO RJ Scaringe:

As much as we’ve seen AI shift how we operate and run our businesses through the wide-ranging applications for LLMs, the potential for AI to really shift how we think about operating in the physical world is, in some ways, unimaginably large.

An explosion of investment like this is never due to just one factor. In fact, several things have come together to produce this moment. Quality robots are getting incredibly cheap. The Chinese supply chain is getting very strong, making it easier for new entrants to build at least a v1 of their products. Hardware expertise is getting more widespread.

Techniques for robotics control and learning have become more mature, and have overcome a few major limitations that we’d seen in the past around mobile manipulation and reliable real-world performance. Partly as a result, companies like Unitree and 1x have demonstrated that there is real demand for robots from consumers, with preorders and widespread hype for 1x and exploding G1 humanoid robot sales for Unitree.

Finally, it seems that the robotics “data wall” is becoming less of an issue. Data collection and scaling is much easier than ever. A number of companies like Build and MicroAGI have appeared to scale up human-centric data collection; research work like EgoMimic has provided at least a feasible route to collecting data at scale (watch our RoboPapers podcast episode on EMMA here). Companies like Sunday Robotics are demonstrating how effective scaling with UMI-style tools can be (see our DexUMI episode on RoboPapers here).

Good Robots are Really Cheap Now

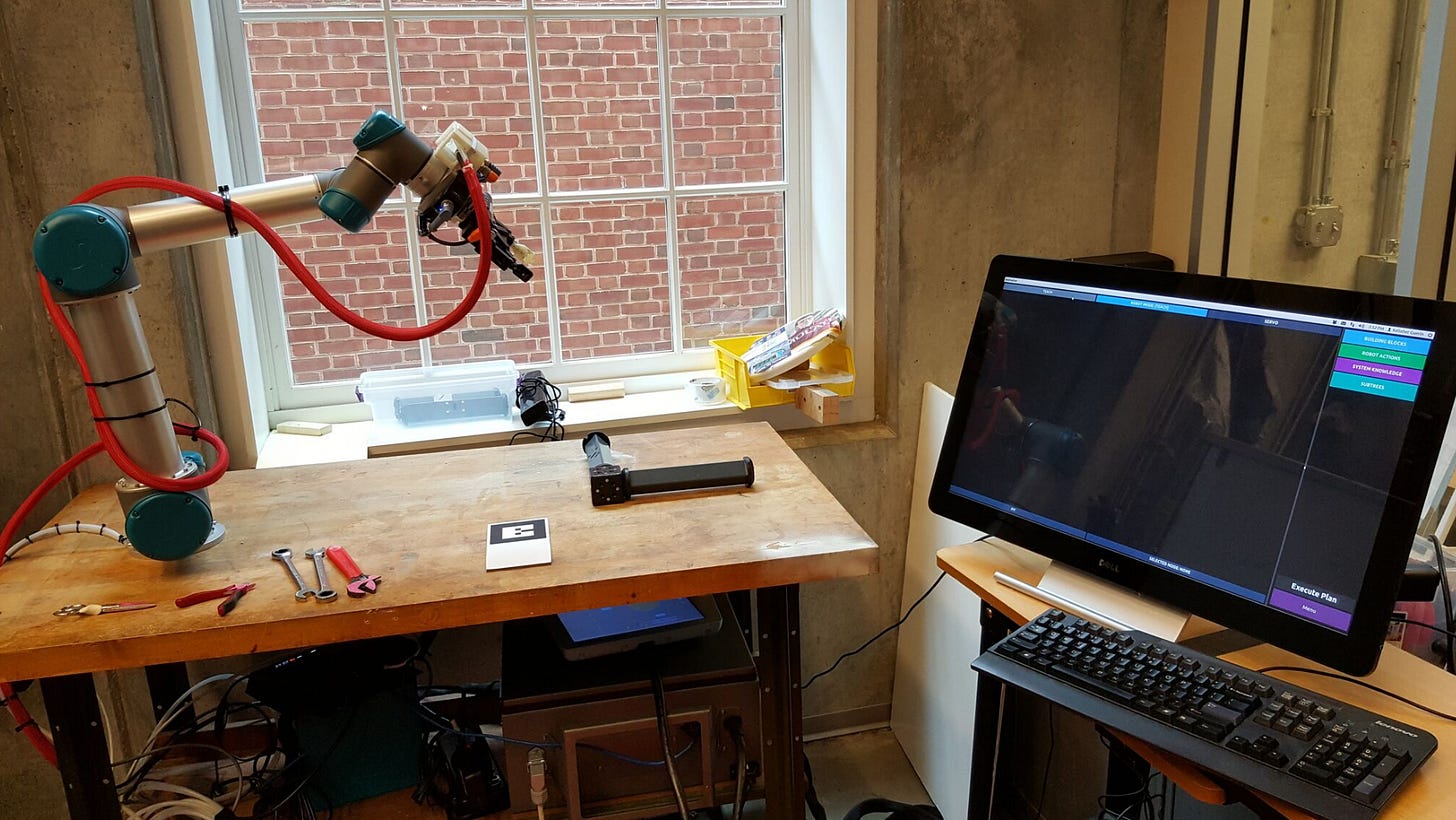

When I was in graduate school, this thing cost like $35,000:

And I’m talking just the robot arm - the Universal Robots UR5 - not the gripper, camera, monitor, GPU, et cetera. It was a pretty good platform, but back then the Robotiq 2-finger gripper alone was also probably about $12,000 — totalling about $62,000 when adjusted for the inflation we’ve seen since 2016.

These days, I could buy four Unitree G1s for that price (base model), or, for a slightly fairer comparison, one Unitree G1 EDU plus. I could also buy a LimX Oli. I will soon be able to buy a Unitree H2, a full-sized humanoid robot (probably $60,000-$70,000 USD, tariffs included).

Buying incredibly powerful, capable robots has never been easier: for less than the price of a mid-range sedan, you now can purchase a robot that was impossible even with DARPA funding just a decade ago. And all of these robots have a much more robust ecosystem: the robotics community has, practically overnight, become absolutely massive. Mass production has given us robots which are both cheaper and substantially more capable — as well as just more fun — than was true less than a decade ago.

And this has downstream effects, because a huge part of what makes it hard to automate stuff just comes down to price! Specialized hardware is expensive, but you need specialized hardware less and less — there are so many more options now. The expertise is more available. The hardware is more robust and easier to use. Lower cost makes the entire robotics ecosystem much stronger than it used to be.

We Now Have a Roadmap to Useful Robotic Manipulation

We’ve all seen a number of incredible dancing and martial arts videos from companies like Unitree. While these are impressive looking, they don’t demonstrate fundamentally useful robot capabilities, because they don’t interact with the environment. It’s relatively easy to program a robot that doesn’t need to collide with stuff; any dumb technique you can think of these days will work for building a robot that doesn’t need to interact with the environment.

Interacting with the environment, though, is tough. It’s hard to simulate; it requires a ton of real-world data to adapt properly. Getting the correct examples of physical interactions is very hard. I’ve spent much of my robotics career working on long-horizon robot tasks, and at this point the problems are very rarely due to high-level planning (the robot decided to do the wrong thing), but more often due to difficulties with environmental interaction.

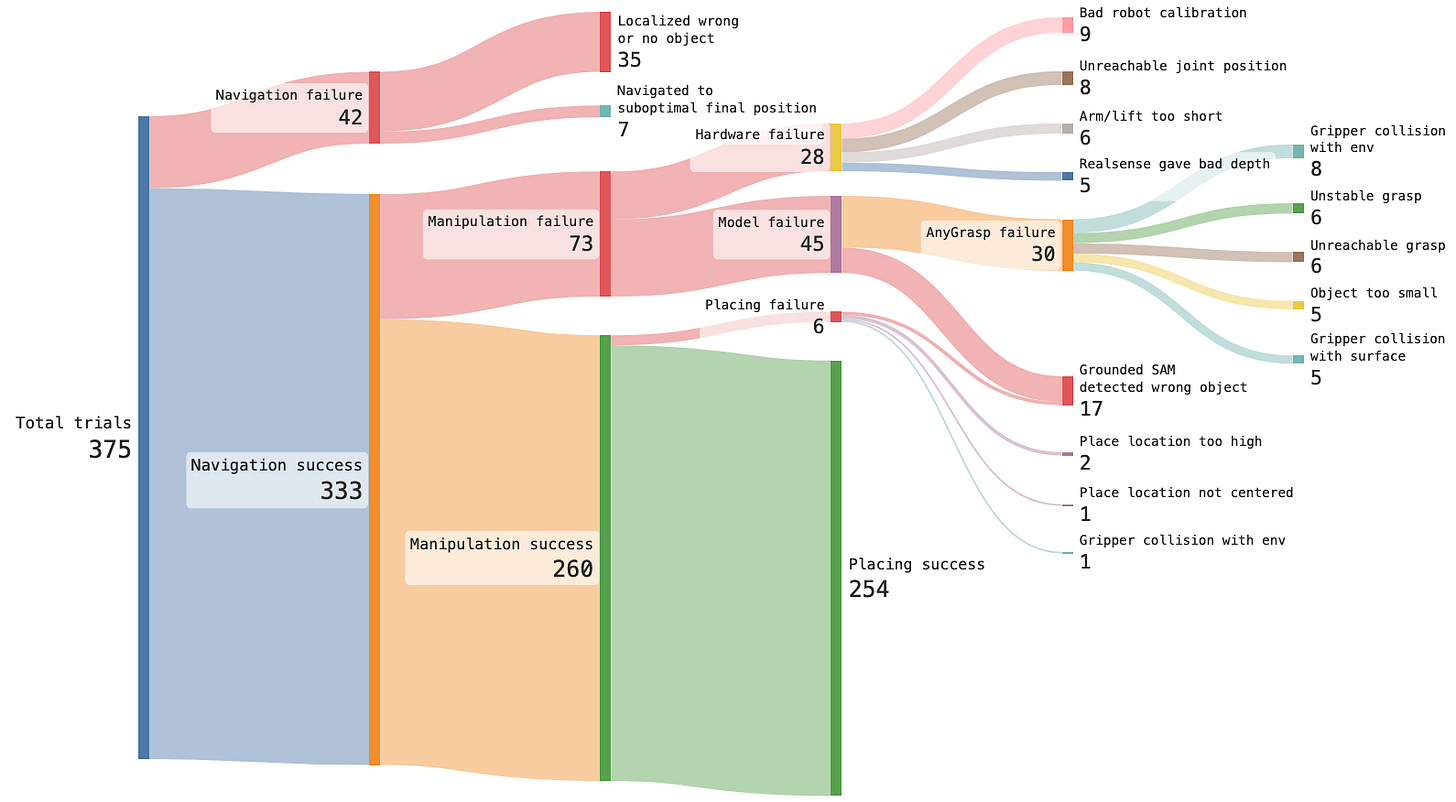

You can take a look at the plot above from the OK-Robot (a 2024 paper) to get a sense for what I’m saying. A lot of the time, the robot can’t reach something (navigation failure); other times the hardware fails; other times it just can’t reliably grasp something due to a model not properly handling the particular combination of environment and object.

If robots could be made to reliably perform real-world manipulation tasks beyond structured picking, this would be a big deal. So I want to draw attention to two specific results that were extremely important this year: whole-body control with mobile manipulation, and real world reinforcement learning.

The video above is from RL-100, recent robotics research from Kun Lei et al. from a variety of institutions but mostly the Shanghai Qizhu Institute. It shows a robot arm working in a shopping mall — an out of distribution environment — while juicing oranges for seven hours.

We’ve similarly seen work like pi-0.6* from Physical Intelligence, which showed robots performing tasks like building cardboard boxes and making espresso drinks, reliably, in a way that humans might. And I’ve already written about folding clothes — startup Dyna Robotics started there but has since moved on to demonstrating high reliability in end-to-end learning with other tasks. Now, none of these tasks are revolutionary on their own, but achieving these levels of reliability with end-to-end systems in the real world absolutely is.

More importantly, the idea that there will soon be a recipe for deploying such skills is crucial. By analogy, look at ChatGPT and the broader adoption of LLMs; previously there were many different image- and text-recognition tools. Model large vision-language models like ChatGPT removed the barrier to building systems that leverage text and images; they provide sort of a shared interface. Even if that means running some on-robot RL procedure where someone types 0s and 1s for failures and successes into a spreadsheet, it seems that we could arrive at similarly highly useful systems for robots.

The Data Wall is Falling

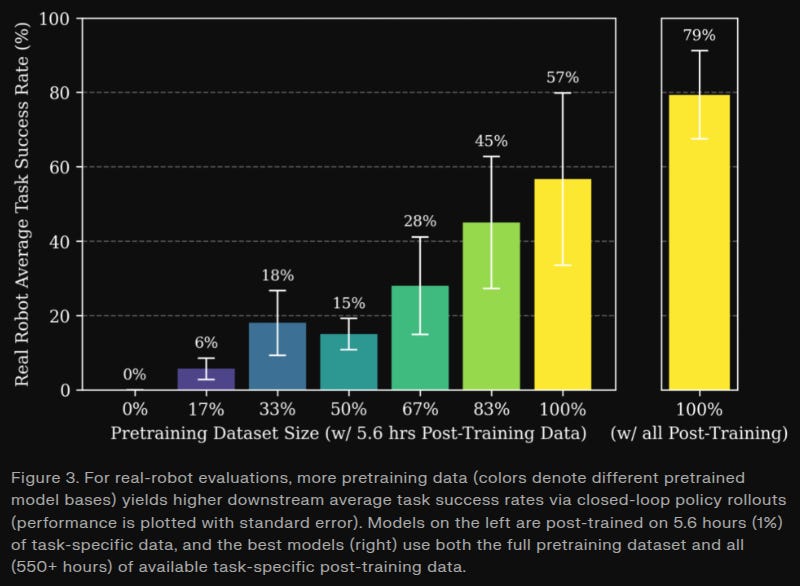

But these advances, just like the ones we’ve seen for large language models, are all likely to be predicated on strong base models, just as we have seen for LLMs. Famously, the reinforcement learning that made Deepseek R1 such a breakout success was only possible because of the quality of pretraining making the reinforcement learning problems tractable.

The base models of robotics are usually called Vision-Language-Action models or sometimes Large Behavior Models (there’s actually a small difference here, but they’re accomplishing the same thing). I’ve also written about it as a direction for future VLA research. The question has always been where to get the data.

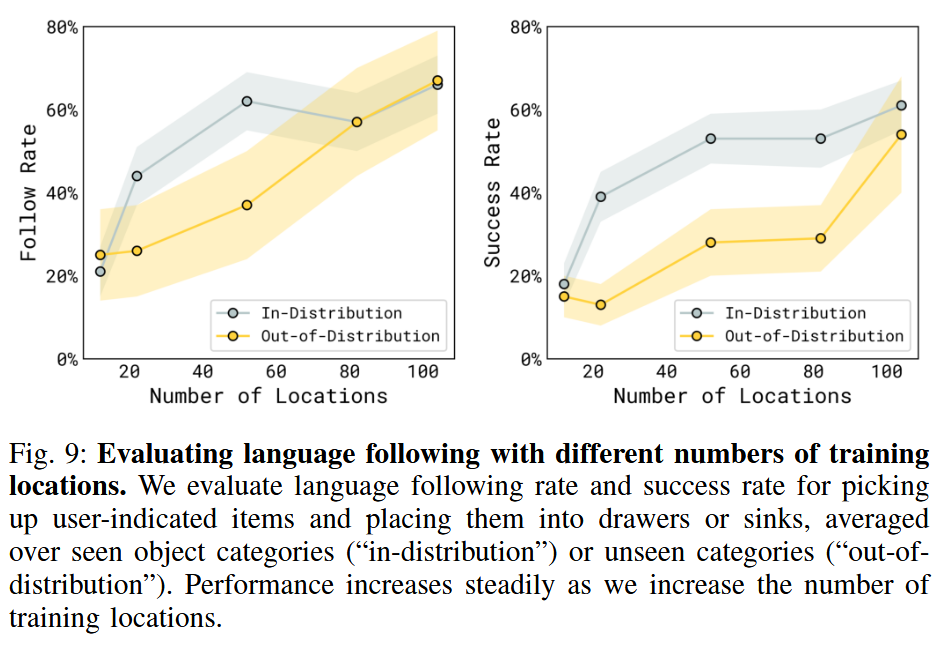

What’s changed is that now broad, diverse robotics data seems achievable, through a collection of different tools. While certain things seemed to be false starts (mass teleoperation data is too expensive, mass simulation often too difficult to tune for contact-rich tasks), there are other really good options which have come into their own this year: egocentric video data and “UMI”-style tool data.

Generalist goes into detail on their recent GEN-0 blog post, describing how diverse pretraining data leads to faster posttraining of their robot models. We’ve also seen from Physical Intelligence that as models scale, they start to learn to treat human data as “just another modality,” meaning that they can start to leverage it to improve performance on various skills. At some point, once we have enough data, this implies that a lot of data-related problems may fall away far faster than previously expected.

A number of companies have sprung up around this idea, including Build, which produces huge quantities of camera-based manufacturing assembly data from human workers, and MicroAGI, which gets rich, high quality data from workers in different industries.

Broadly, it seems more likely than ever that the “eternal” robotics problem of not having enough data, will be solved in the coming years. And unlike in my previous estimates, I no longer believe it will necessarily be some billion-dollar project — which means many companies will be able to build powerful autonomous systems.

The Elephant in the Room: LLMs

Large language models have also made dramatic progress in the last year. OpenAI’s o1 — the world’s first “reasoning model” - launched towards the end of 2024. Its success led directly to the release of Deepseek R1, which was a spectacularly important paper that described publicly a lot of the “secret knowledge” kept in house at OpenAI and has allowed for waves of successive exploration.

And the changes have been extreme. Coding is incredibly different from what it was just a year ago; it will likely never be the same again. Never again will I just write a whole project, token by token, by hand. These changes are appearing in many different industries: people raise concerns about AI replacing lawyers — increasingly many lawyers just draft everything with ChatGPT anyway. Similarly, 67% of doctors use ChatGPT daily, and 84% of them say it makes them better doctors. GPT 5.2 was evaluated on GDPval, a set of economically-valuable tasks, where it achieved equal or better performance than an in-domain human expert 70.9%.

Large language models are already significantly changing the way people work and rewriting the economy, like it or not. And these changes seem to be propagating far faster than the changes we saw with automobiles at the beginning of the 20th century, having propagated through society with all the speed of the internet. Robotics won’t spread so fast, but unless serious obstacles manifest (such as a total collapse of funding for R&D), it seems plausible there will be similar changes in the physical world.

The Next Few Years in Robotics

To go back to the metaphor at the start of this blog post: when horses vanished from American cities, they didn’t just lose their jobs. The whole infrastructure of cities changed: hay and stables were replaced by gas stations and parking garages. Manure was gone from the streets, replaced by exhaust fumes. The feel of a city, even walking around on foot, now revolves around cars, with wide, flat asphalt roads and traffic lights on every block. Similarly, if the “optimistic case” from this blog post holds true, we should see significant changes in the fundamental details of life.

So, to recap: we have seen a year of dramatic robotics progress which for the first time showed the viability of long-running end-to-end robotics manipulation, at the same time the cost of robotics hardware is collapsing and its quality is exploding. We have seen dramatic changes in the world of purely-informational artificial intelligence, through reasoning models and agents.

I believe I have motivated this “optimistic case” well enough now that I am allowed to speculate a bit, as I promised at the beginning of this blog post. To start, we may make a couple assumptions about robotics over the next several years:

The robotics “data gap” will continue to close, and robotics will start to pick up speed due to the combination of more robots and more tools for making robots possible to use and deploy

AI will be at the heart of this — both reinforcement learning and imitation learning will be key parts of the solution, as elaborated in my previous blog post on VLA research directions

This means that a lot of areas of robotics which were previously inaccessible to automation soon will be. In fields like construction, we have thus far been limited to incredibly simple and structured pieces of automation: specially-built roofing robots, for example. Similarly, much of manufacturing is already automated, but that automation relies heavily on specialized systems, sensors, end-effectors, and machinery. All of this makes automation extremely expensive.

At the same time, the labor markets for fields like construction and manufacturing are getting worse. The world has filled up in a way; our countries are graying. We expect the ratio of workers to retirees to go down, requiring each individual worker to be far more economically productive. Those same retirees will need care and companionship that humans are unlikely to be willing or able to provide. All of this means that the world of 2030 will be far more robotic than that of today.

By 2030, users will be able to create and share their own use cases, as this is where true explosive growth starts to happen.

I expect we will see far more robots essentially everywhere. Waymo and its competitors will expand to more and more cities; fewer people will use their personal vehicles to get around. If they do, their vehicles will be using Tesla or Wayve autopilot systems to get around.

Robots will be in homes. They may or may not be humanoids. But they’ll be able to perform a wide range of simple manipulation tasks, things like picking up and perhaps putting away the dishes. They’ll cost less than a car, possibly in the $10,000-$20,000 range for a very good one. Robot production will still be ramping up this point, so it’s probably still less than 1% of households that have an in-home robot — but it’s going to be rapidly increasing into the 2030s, until it reaches similar levels to cars by 2040, with 50% or more owning an in-home robot that can help do chores.

These home robots will often be companions first; modern AI is extremely good at companionship. It is striking to me how much for example my two year old daughter likes to interact with even very simple home robots like Matic and Astro; more capable and intelligent LLM-powered home robots will be far more compelling friends and “pets.”

Most importantly, this will also lead to the “iPhone moment” for robotics, which is when acceleration will really take off. Some — such as Sunday Robotics founder Tony Zhao — have publicly alluded to this moment coming. What we hope is that by 2030, users will be able to create and share their own use cases, as this is where true explosive growth starts to happen.

In manufacturing and industry more broadly, we’re already seeing “systems integrators” start warming up to widespread use of end-to-end artificial intelligence. As the core technical competencies for deploying robotics models and post training them for specific tasks start to diffuse, I expect this to become very common.

Perhaps by 2030, you will order a set of robots for your factory and hire a consultant to train them for a couple days if you’ve never done so yourself. Eventually, though, this seems like an economic efficiency that will largely be done away with. You don’t usually hire an external contractor to integrate an LLM into your workflows; robots should be no different.

I started this post with an anecdote about horses being replaced by the automobile, but so far I really haven’t discussed what, exactly, the horses are that are being replaced. These metaphorical horses aren’t people, not exactly, but they are jobs currently done by people. Software engineering, for example, is clearly harder to break into now than it used to be. An individual experienced programmer is so much more productive with AI as a “force multiplier,” which means that less people are necessary to build and deploy complex software products.

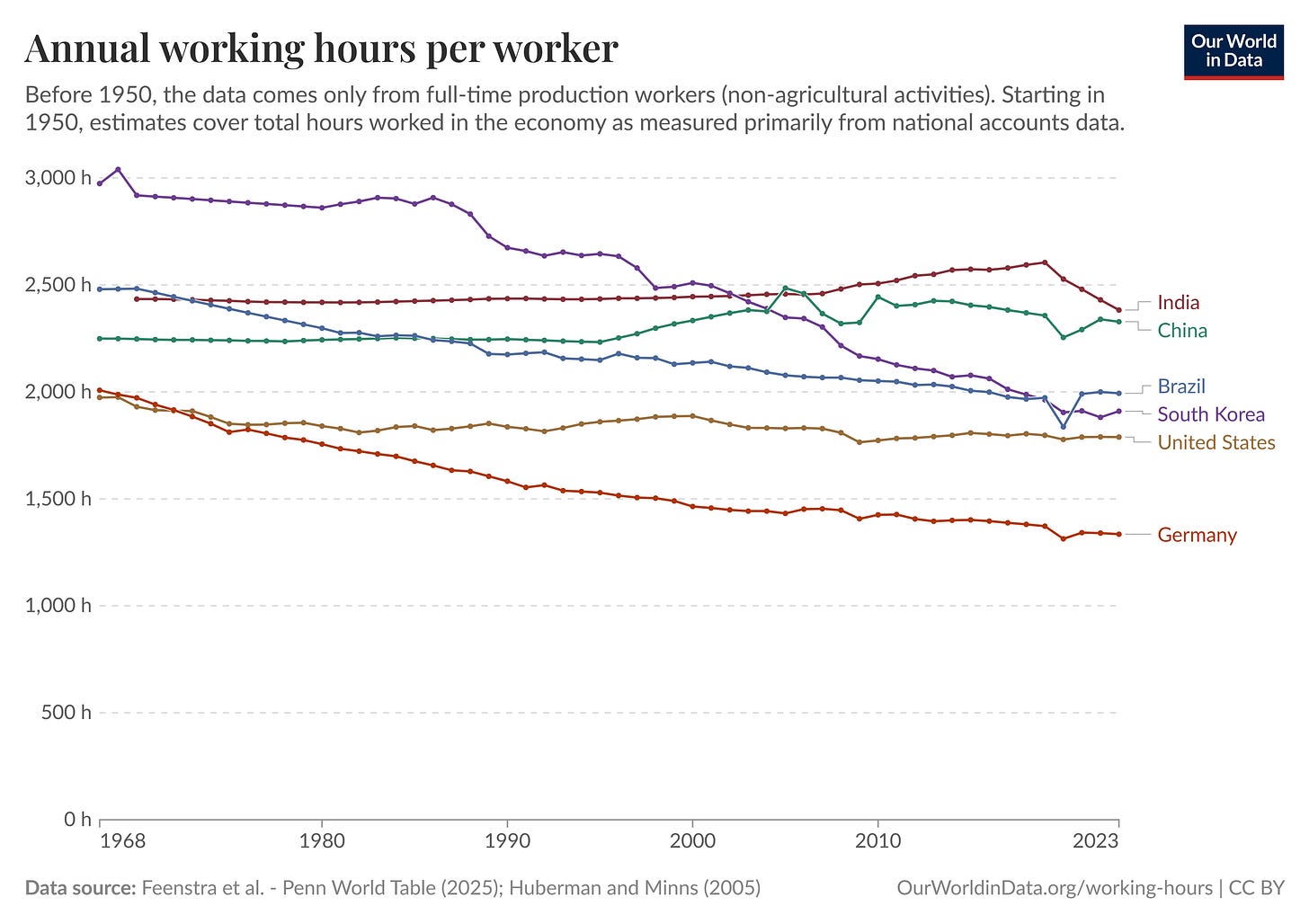

We should expect to see similar trends across basically every industry: more highly paid experts being far more productive, building more things, but each individual set of expertise being basically priceless, with robots handling more and more of the easily-replaceable labor. We should not fear this: in the developed world, working hours have largely been on a downward trend for decades, and it seems likely this will continue. Many human jobs will amount to handling the long-term planning and coordination that AI and robots seem persistently bad at, and intervening when they fail; but this should make for comparatively easy and low-stress work for a great percentage of the workforce.

Reasons for Doubt

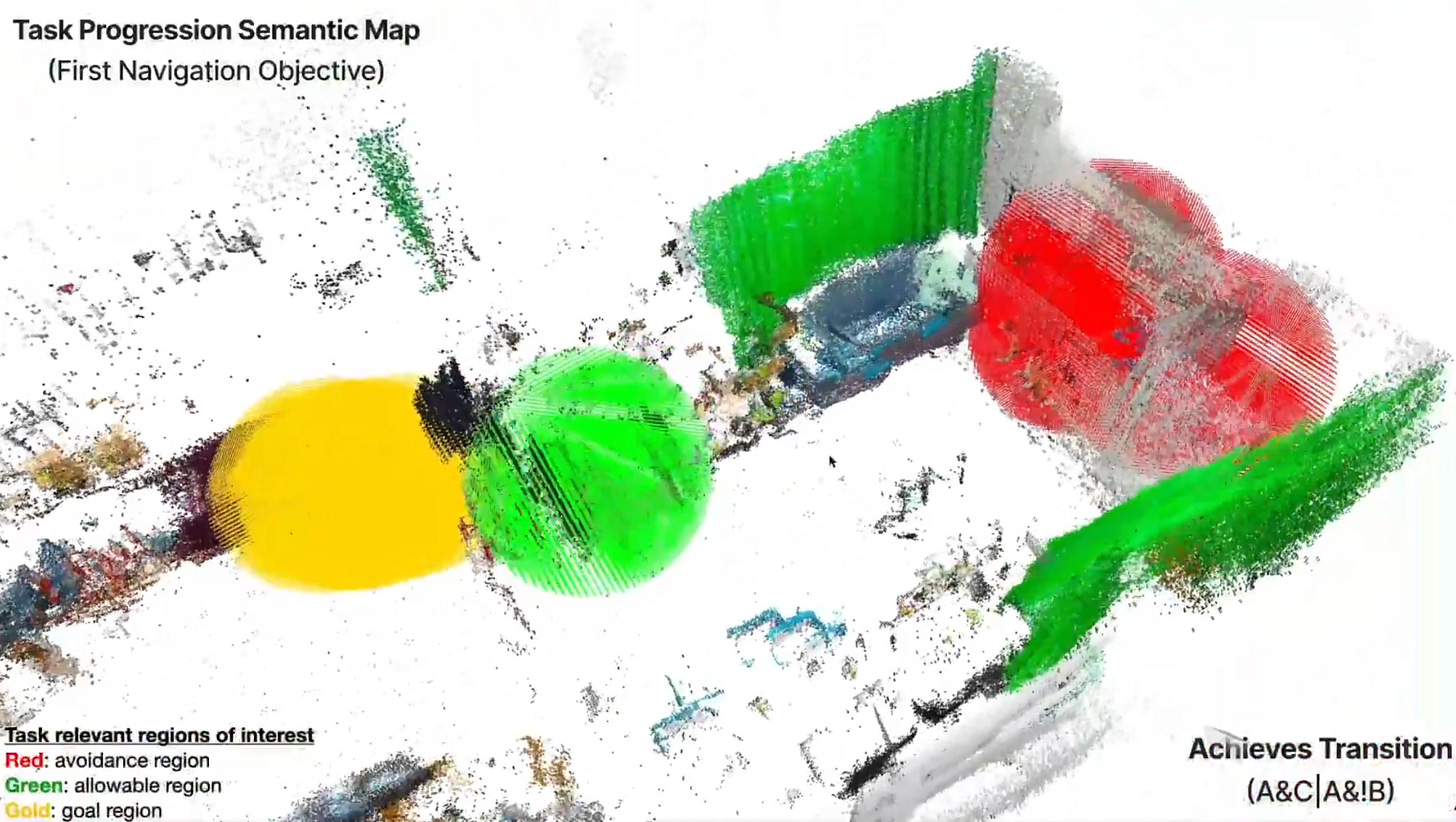

It’s strange to look back at my own predictions for robotics from the end of 2024. Back then, one of my chief concerns was how to build scalable “world representations” for long horizon reasoning. This remains a concern to me; I’ve honestly seen basically no significant progress in this space. There are impressive 3d world models now, like that of World Labs, but these are all generally creating single scenes, not modeling their evolution in response to new sensor data. For true embodied general intelligence, we still need to address these fundamental questions about how robots will represent their knowledge of the world over time.

In some ways, it’s a good thing: the blocker for deploying long horizon reasoning has never been that long horizon reasoning is all that hard, it’s always been that execution is hard and that robots break (see, again, the Sankey diagram above from OK-Robot).

This also will still require lots of funding. Fortunately, it seems that many investors and billionaires with deep pockets — Jeff Bezos, Elon Musk, and others — are “all in” on artificial intelligence and robotics. Very likely, the money will not run out. But if it does, all this could come to a premature end.

And finally I worry about the closing-off of ecosystems. Open robotics innovation right now is championed, largely, by Physical Intelligence and NVIDIA, with some great recent entrants from Amazon FAR. While many of these problems are being solved, we still need new ideas and open dialogue to solve them — if all our doors and windows close, it’s possible the field stagnates and nothing gets accomplished.

Final Thoughts

With robot hardware getting so much better, with methods becoming mature and real-world results and long-running demos becoming somewhat common, I’ve never been more optimistic about what robotics will be capable of.

Part of the point of writing this is to point out how fast things have changed. And this is not unprecedented! I started this blog post with an anecdote about the horse being replaced by the automobile over just a couple decades. It’s not unreasonable to think that — in a lot of ways — we’re heading for such a moment. Not next year, not in two years, but over the next decade? It seems inevitable.

Basically all robotics problems get easier at scale: hardware related, deployment related, and data related issues all become much more tractable as soon as there are a lot of robots out there in the world.

I believe very strongly that we’re on a great trend, that these technologies will diffuse through society over the next 5-10 years, and that the future bright. But we’re headed for a very different world than the one we live in now, and that’s something we’ll also need to wrestle with over the coming years.

Love the horse analogy as a framing device. That stat about NYC going from 130k horses to essentially zero in adecade really puts current robotics trajectory in perspective. The argument about lower costs enabling the ecosystem is spot on, I remeber when a UR5 setup would blow a whole research budget. Now seeing end-to-end RL actually working reliably (like that orange juice example) feels like watching ImageNet moment happen all over again, just in phyiscal space this time.