Paper Notes: Nested Learning

A research paper from Google on how to enable AI to learn over its lifetime without a distinct "training" phase

Google has a new paper called Nested Learning which aims to enable lifelong learning in artificial intelligence by framing the machine learning optimization problem as a set of nested sub-problems [1]. In the authors’ words:

We introduce Nested Learning, a new approach to machine learning that views models as a set of smaller, nested optimization problems, each with its own internal workflow, in order to mitigate or even completely avoid the issue of “catastrophic forgetting”, where learning new tasks sacrifices proficiency on old tasks.

For robots and other artificially intelligent agents to be deployed “in the wild,” they will need to be able to learn on the fly, while not forgetting all of the other things they’ve already learned.

The way we usually do this right now is through clever tricks of context; for example, when you talk to ChatGPT, it will save additional memories as text. I actually have a really dumb version of this implemented in a Discord chatbot here if you want to see how well it works by experimenting on your friends and family.

But this has its limits. Context lengths grow, and memories require more and more “compression.” This form of memory is essentially just a more elaborate system prompt in a lot of ways, and so nothing fundamental will change. Ideally, we would see a version of this where the weights of the neural network themselves change over time, something more like how humans learn over time.

This is a problem we call Continual Learning or Lifelong Learning. If you want to read a bit more about continual learning in computer science, and what it might mean for human learning, you can check out this blog post by Beren Millidge called “Continual learning explains some interesting phenomena in human memory.”

The core insight in this work is that by treating the whole AI learning problem as a set of nested sub-problems, which makes it possible to avoid a crucial issue with current continual learning approaches. Let’s go lightly over how.

This is pretty different from my usual type of post, so maybe take a look at some other posts before clicking subscribe below (like this one or this one):

The Problem: Catastrophic Forgetting

The core problem we want to solve with lifelong learning is called catastrophic forgetting. Let’s walk through a naive solution to see why.

Imagine I have a neural network which I’ve trained to perform some task, like say pick up cups around my house and put them back in the cabinet. I’ve collected a great dataset for cups: I have a whole variety of cups of different sizes and shapes and colors. I have all the places where they might go: these go in a cabinet, these fancy cups in a display case, and so on. Great. Call this dataset A, and assume I have some policy trained on this A.

Now, I extend this with new data to pick up toys off of the floor and put them in their boxes. I collect a new dataset with all kinds of children’s toys: action figures, stuffed animals, whatever. With them I collect a new dataset of demonstration locations to place these objects. Call this dataset B.

I continue training my model, which was originally trained on A, but now I am only training it on B. Unsurprisingly, when I next try to train on A, I see that I’ve now lost all performance on A — my robot can no longer put away cups properly.

Now, I already know the solution to this: I have to train on both A and B. The problem is that as I add more datasets — C and D and E and so on — the amount of data that I have to train on becomes cumbersome. I start to run into model capacity issues, or inference becomes slow, or I just can’t train on all of these fast enough.

Realistically, I want some way of updating my policy with a new dataset without hurting its performance on old datasets, but also without fully retraining on all my various datasets. The naive solution here — the most common and usually best solution — will be to just sample from all of the different datasets so I’m always retraining on a little bit of everything, according to my other constraints.

But that’s an awkward solution that requires you to store infinite data forever, so let’s see if these Google researchers can come up with something better.

Nested Learning as a Solution

In general, we solve this problem through modularity. In what limited work I’ve done on continual learning [2], for example, the proposed method resulted in multiple parallel robot policies, each of which was specialized to a different setting.

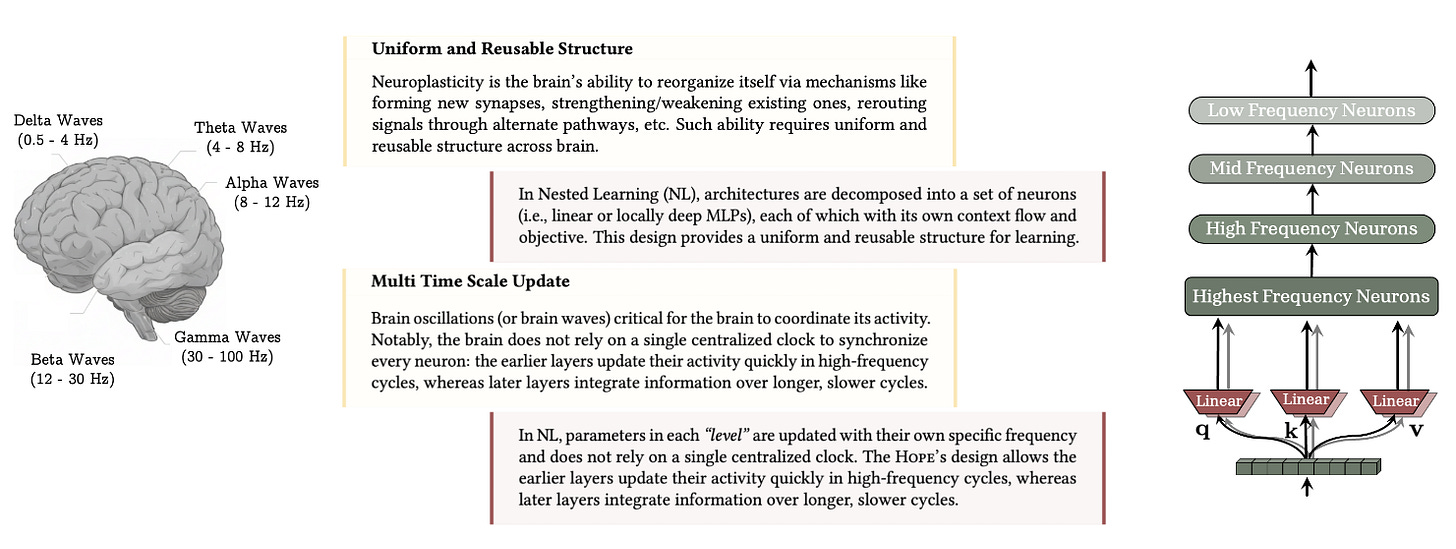

But that’s not really how the human brain works. We have memory that operates at many different scales: some longer term, some shorter term. Current transformers only experience the present: they basically have some baked-in knowledge encoded in weights, and they have their context, and that’s it.

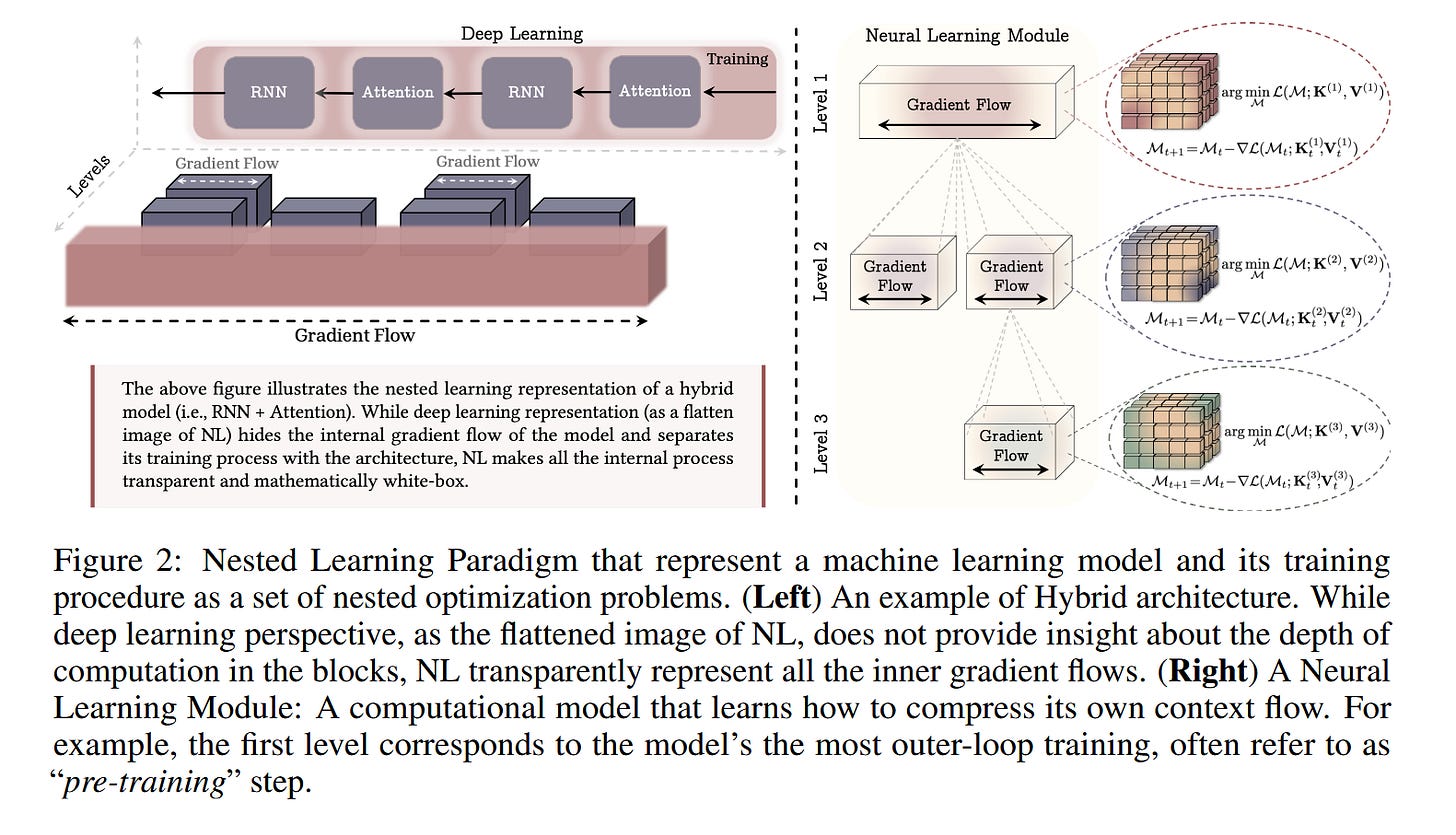

The key insight here is that momentum-based optimizers like Adam are, in an of themselves, a sort of associative memory — basically a model. And so we can pose a learning problem as a set of nested optimization problems, all running at different speeds:

Inner loops update rapidly to capture new information (like the locations of the toys we wanted to grasp, from our example above)

Outer loops update slowly, capturing more general information (the structure of the home, perhaps).

This means that the slower outer loops can anchor new information and prevent the model from forgetting everything.

Associative Memory

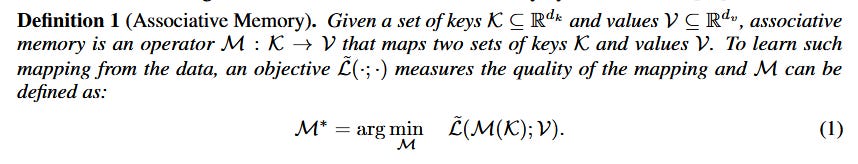

The core claim of the paper is that architecture is an illusion: that both optimizers (Adam, for example) and neural networks are the same thing: an associative memory. Since we will be talking a lot about learning and memory, the authors provide us with this helpful definition:

Memory is a neural update caused by an input, and learning is the process for acquiring effective and useful memory.

An associative memory, then, is going to be something which maps between different sets of keys and values:

This is an incredibly broad definition, which is sort of the point. So Attention is an associative memory mapping tokens to other tokens; Momentum (as in SGD) is a memory mapping gradients to updates. Optimizers like SGD are just very simple associative memories, which the authors proper replacing with “Deep Optimizers” that learn how to update inner networks.

So, training a single neural network as building a mapping between the data points in your training dataset and their local surprise signal in representation space (i.e. how well they match their objective), just over the training dataset examples.

This part is pretty straightforward interpretation of LLM training. Where it gets more interesting is in the next layer; a momentum-based optimizer then becomes a second-level associative memory, where the outer layer is updating the weights with based on the inner-level memory (again, basically prediction error).

We can follow this logic to phrase a machine learning problem as a set of nested optimization problems, where at each level it isn’t just learning a task but also learning how to learn the task. These levels all operate at different update rates — again see the analogy to the human brain above — with outer/higher level loops updating less frequently.

The HOPE architecture

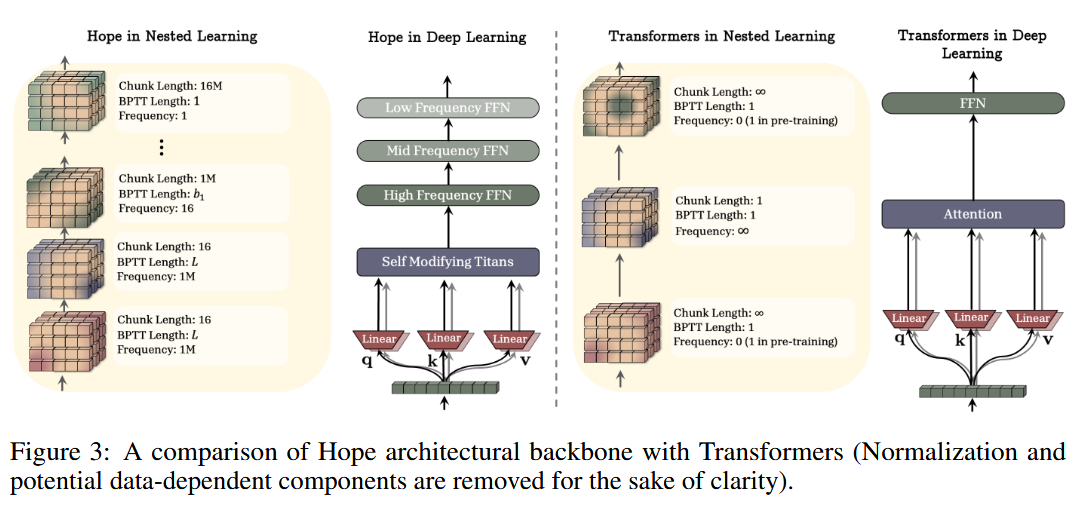

The authors go into more detail talking about how they can represent many well-known optimizers as special cases of nested learning, and go on to propose more expressive versions of optimization and of the underlying memory operation. They also propose HOPE.

HOPE is a “Self-Referential Learning Module with Continuum Memory,” which here means that it’s a chain of neural network blocks updated at increasing frequencies as they are nested deeper and deeper. To understand why, let’s consider the case of learning a Transformer for language prediction.

In a “normal” Tranformer trained with a discrete train and eval phase, we have two time frequencies that we care about; general, high level information is only encoded once, at training time, and local information is only encoded in the context window (hence in-context learning). But with HOPE, we have many modules, each learning how to update the one below it, and operating at different rates, which makes it much more adaptable.

Their proposed architecture builds on Titans [3]. Titans are a new class of model designed to improve memory, enabling remembering and forgetting over time (remember this is generally not something transformers do — they just rely on their long context windows!).

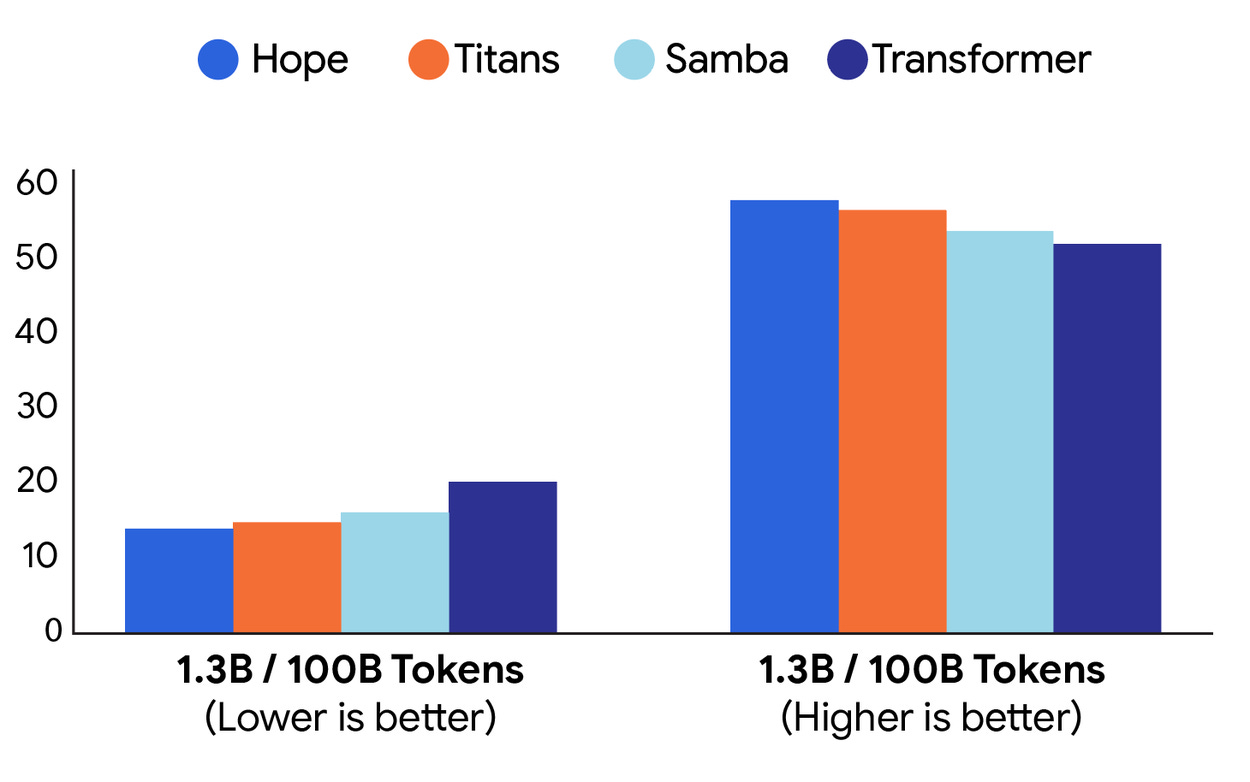

While this is all extremely preliminary machine learning theory, the results look promising for language modeling:

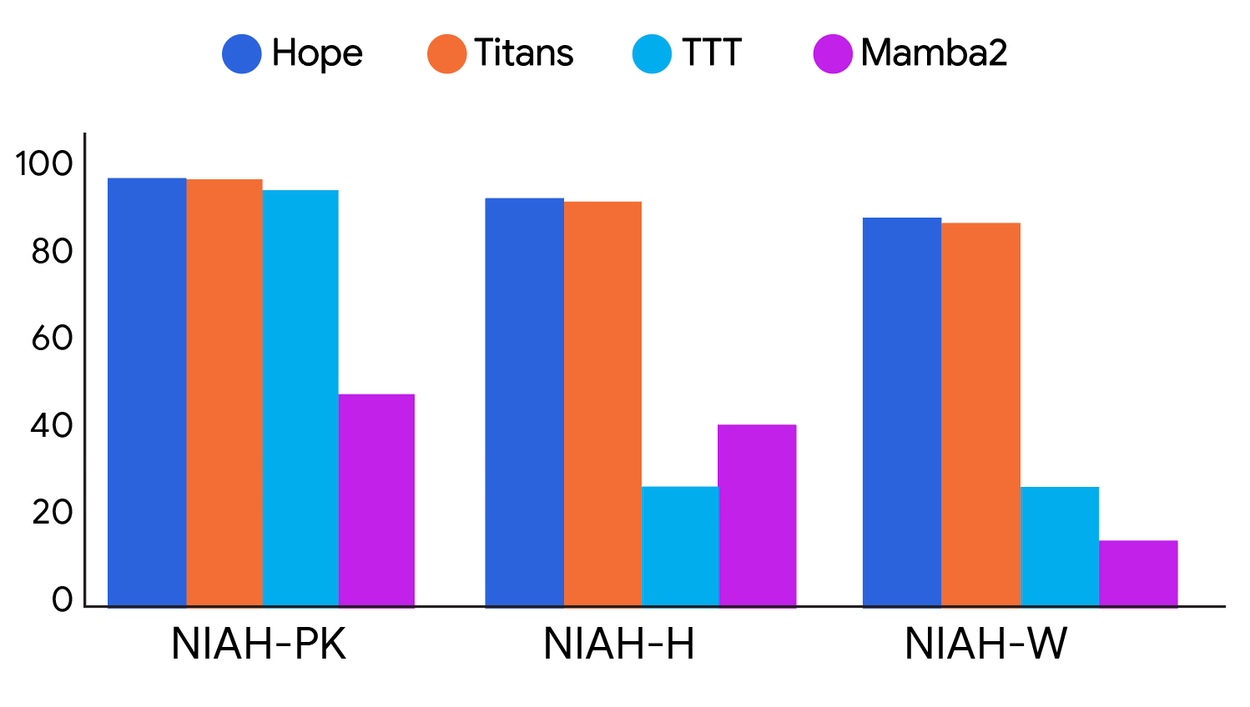

And for increasingly difficult long-horizon tasks:

Final Thoughts

There’s an interesting line of work around “what comes after the transformer?”

Transformers are, inherently, extraordinarily limited in ways that may be surprising: context length, tokenization requirements, and so on. Many methods have been proposed to address this, like state-space models and Mamba (which appear in the charts above). Fundamentally, it seems that at some point, transformers will stop scaling; so these types of architectures are appealing. And a model which can essentially keep training all the time, and operates at different training “speeds” so as to avoid things like catastrophic forgetting, seems valuable.

As usual though, with a theory paper like this, it’s worth noting that these seem fairly far from use on anything more than toy tasks — and that inference with transformers continues to improve, in part because they scale extremely well. Titans and HOPE won’t be replacing GPT next year or anything.

But the idea here — that we’re thinking about neural networks wrong, that “optimizers” and “modules” are not actually discrete entities — seems extremely interesting and has a ton of potential for the future.

References

[1] Behrouz, A., Razaviyayn, M., Zhong, P., & Mirrokni, V. (n.d.). Nested learning: The illusion of deep learning architectures. Google Research.

[2] Powers, S., Gupta, A., & Paxton, C. (2023). Evaluating continual learning on a home robot. In S. Chandar, R. Pascanu, H. Sedghi, & D. Precup (Eds.), Proceedings of The 2nd Conference on Lifelong Learning Agents (pp. 493–512). Proceedings of Machine Learning Research.

[3] Titans: Learning to Memorize at Test Time. Behrouz, A., Zhong, P., & Mirrokni, V. (n.d.). Titans: Learning to memorize at test time. Google Research.

Why isn’t continual fine tuning of transformers on individual user corpuses more common?

The analogy to how the human brain handles memory at different timescales is really stricking here. Most attempts at lifelong learning feel forced, but this nested optimization approach seems much more naturla. I wonder if the trade off in computational cost will be worth it though, since transformers are so efficient at infrence right now.