The Role of Open Source in Robotics

Open source software has always played a crucial role in robotics, and that role has continued to evolve with the robotics field

Getting started in robotics, as anyone will tell, you, is very hard.

Part of the problem is that robotics is multidisciplinary; there’s math, coding, hardware, algorithms; machine learning vs. good-old-fashioned software engineering, etc. It’s hard for one person to manage all of that without a team, and without years to build upon. And at the same time, there’s no “PyTorch for robotics,” and no HuggingFace Transformers either. You can’t really just dive in by opening up a terminal and running a couple commands, something that the broader machine learning community has made beautifully simple.

Sure, you could download a simulator like ManiSkill or NVIDIA Isaac Lab, run a couple reinforcement learning demos, and end up with a robot policy in simulation, but you still need a real robot to run it on, like the SO-100 arm.

And yet open robotics, in a way, is at a turning point.

ROS1 — the venerable, old Robot Operating System which raised a generation of roboticists, myself included — is gone. Dead, due to be replaced by ROS2, which has had a mixed reception, to say the least. It’s got a number of issues, and in particular is fairly cumbersome for development.

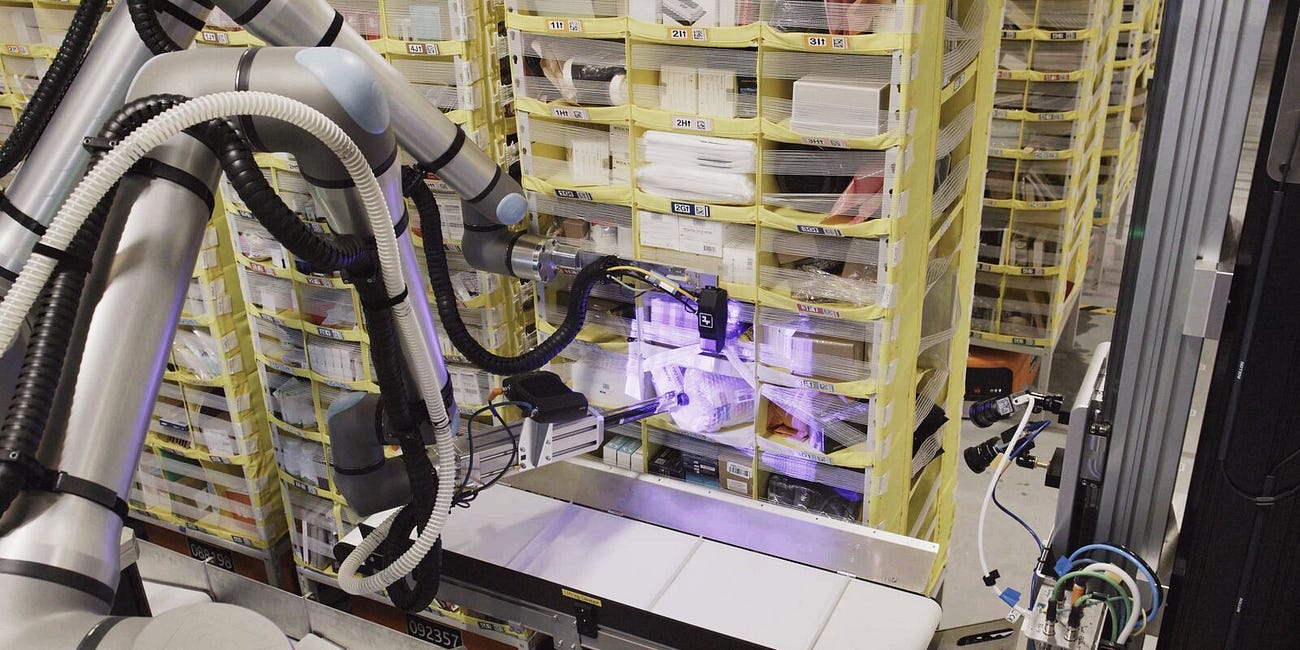

And, in parallel, the accessibility of high-quality and affordable robot actuators (largely manufactured in China) has collided with the proliferation of 3D printing, to cause a Cambrian explosion of open-source hardware projects. These projects are making robotics accessible at the lower end, letting people outside of well-funded robotics labs and universities experiment with end-to-end robot learning capabilities.

This has all led to a new wave of open-source robotics projects, a Cambrian explosion of new robotic hardware and software that’s been filling in the gaps in current hardware and software, and making robotics accessible for tooling that works very differently from previous generations of hardware and software.

A Recent History of Open Software

The Robot Operating System, developed largely by the legendary Willow Garage robotics incubator before its dissolution, used to be a center-of-mass for open robotics. Largely, now, this has been replaced with a much more python-centric and diffuse ecosystem, prominently featuring model releases mediated by HuggingFace and its fantastic array of python packages and open-source robotics code.

ROS, at its heard, is and was a middleware, a communications layer which made it easy to coordinate different processes and disparate robotics systems. This was crucial in the era when most robotics development was fragmentary and model-based: you need to move your robot around, you need a SLAM stack like Nav2, which was formerly a part of ROS.

But as software development has gotten easier, driven in part by the fast-moving python ecosystem and ML culture, as well as by the explosion of open-source and readily usable packages on Github, we’ve seen ROS fade from prominence.

There’s no real replacement, nor should there be. Cleaner software interfaces which just accept Numpy arrays, ZMQ for messaging (as we used in StretchAI), and so on make it very easy to accomplish the goals of the old ROS without the inflexibility.

And this all means that now we can see a vibrant, decentralized open source ecosystem, largely building off of LeRobot. For example you can check out ACT-based reward function learning by Ville Kuosmanen, installable via Pypi:

In the end, I think this is a much better model. While pip has its weaknesses, the decentralization and simplicity of the system means that you can, for example, replace it with something like astral’s uv when it comes along.

Visualizations from companies like Foxglove and rerun have also expanded into the niches that ROS’s aging rviz is vacating. Rerun in particular is fully open source, and extremely AI friendly with powerful, flexible, and easy-to-use APIs that make visualizing learning data easy — presumably why it’s also a feature of LeRobot.

My own contribution to all of this is Stretch AI, a software package I released last year which makes it possible to do long-horizon mobile manipulation in the home. Part of this is support by Peiqi Liu for DynaMem, which allows a robot to move around in a scene dynamically build a 3d map which can be used for open-vocabulary queries. This is built on top of, in part, many of these tools, from ROS2-based robot control software, python-based custom network code, Rerun visualizations and a variety of open models and LLMs.

Introducing Stretch AI

I'd like to introduce Stretch AI, a set of open-source tools for language-guided autonomy, exploration, navigation, and learning from demonstration. The goal is to allow researchers and developers to quickly build and deploy AI-enabled robot applications.

Open Hardware

One increasingly fascinating trend has been towards open hardware.

HuggingFace has recently been a great champion of this, building HopeJr, their open-source humanoid robot. And they’re hardly the only one, with K-Scale’s open-source humanoid soon to follow.

But open source hardware is particularly useful where there isn’t a clear scientific consensus on what the correct solution is. This is why, for example, I covered a lot of open-source tactile sensors in my post on giving robots a sense of touch:

Giving Robots a Sense of Touch

While we humans are, largely, visual creatures, we can’t solely rely on our eyes to perform tasks. This is a contrast to most modern robotics AI, for which the best practice i…

We’re seeing the same thing happen with hands. Robot hands are an area that has been sorely in need of improvement; current hands are broadly not very dexterous. New hands, like the Wuji or Sharpa hands, are extremely impressive but are still very expensive and not too broadly available.

This has led to a ton of iteration in the open source space, like the LEAP hand:

We also see the RUKA hand from NYU, which again is cheap, humanlike, and relatively easy to build. Projects like the Yale OpenHand program have been trying to close this gap for a long time.

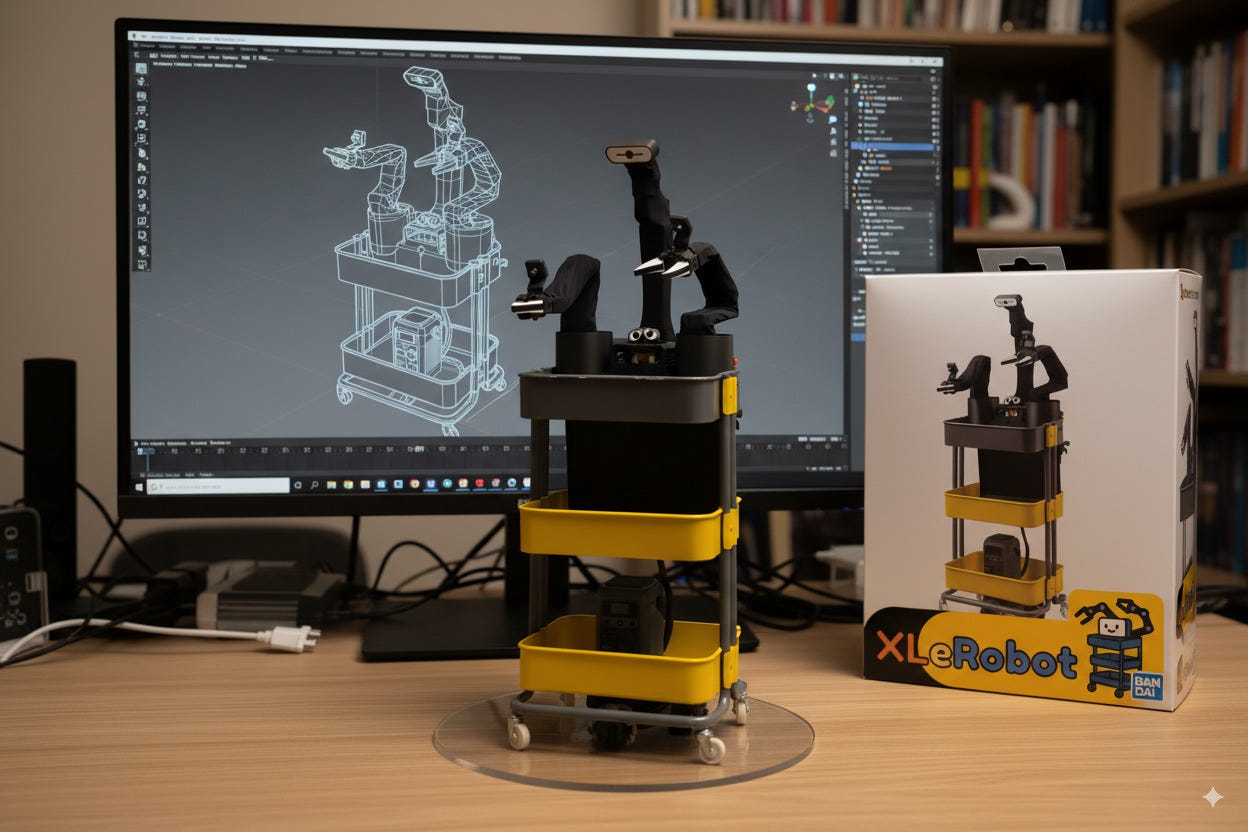

And we can see a similar thing with robots. There are the So-100 arms, LeKiwi, and XLeRobot. Other notable projects include OpenArm:

This is a fully open-source robot arm, with a BOM (bill of materials) cost of about $6.5k. Find the OpenArm project website here, or a thread by Jack with more information. And, of course, open-source champions at HuggingFace have been working on a variety of open humanoids.

All in all, robotics is still at a very early point - so it’s great to see people iterating and building in public. These projects can provide a foundation and lots of valuable knowledge for further experimentation, research, and commercialization of robotics down the line.

What’s Still Missing?

There are lots of cool open source projects for hardware and foundation models, but there are still relatively few large open-source data collection efforts. Personally, I hope that organizations like HuggingFace, BitRobot, or AI2 can help with this.

And in addition, I think we still really need more good open-source SLAM tools. SLAM, if you don’t know, is Simultanteous Localization and Mapping — it’s the process of taking in sensor measurements and identifying the robot’s 6DOF location in the world.

Everyone is using iPhones (DexUMI) or Aria glasses (EgoMimic, EgoZero), or just like a quest 3 or whatever to do this right now — see the Robot Utility Models work, or DexUMI, which we did a RoboPapers podcast on. A lot of the tools exist — like GT-SLAM — but it’s still too hard to just take and deploy on a new robot.

The Future of Open Source in Robotics

We need open robotics. Even those of us working in private companies — like myself — will always benefit from having a healthy, strong ecosystem of tools available. All of us move much faster when we work together. And, more importantly, it helps the small players keep up. Not everyone can be Google, a single monolithic company.

As open-source roboticist Ville Kousmanen wrote:

An open source Physical AI ecosystem offers an alternative to commercial models, and allows thousands of robotics startups around the world to compete on equal footing with Goliaths hundreds of times their size.

Open source is also powering what I think is my favorite trend in robotics lately. You can actually run your own code on others’ robots! Physical Intelligence has released it’s new flagship AI model, pi0.5, on HuggingFace, which leads to fast open-source reproductions:

This video is from Ilia Larchenko on X, who we recently interviewed on RoboPapers (give the podcast a listen!) and who is a feature of the fast-moving open-robotics community. And you can even deploy open vision-language-action models like SmolVLA on open-source robots like XLeRobot and get some cool results. Even German Chancellor Friedrich Merz is getting in on open-source robot action!

I’m happy to see how lively and dynamic the modern open-source robotics ecosystem has become, helping make robotics more accessible for students, researchers, startups and hobbyists than ever before.

Hi Chris, speaking of SLAM, do you think it still an essential component during this VLA era?

what do you think about Cerulion ? ( cerulion.com)