Why Not Everything is Automated in Manufacturing (Yet)

Even in an era of AI and dark factories, automation is lagging behind promises, particularly in the United States. Why is this happening?

The future of industrial production is automated. From our ports to trucking and last-mile delivery, robots are now involved in nearly every part of bringing people the products that they want. And yet in a lot of cases the production of these products themselves is not yet automated; they are still built by specialized human workers. Even in wealthy, developed countries like the United States many things that seem as if they should be automated are not.

Take the example of Nike trying to near-shore production of shoes from Vietnam to Guadalajara, Mexico, as described in this Wall Street Journal article by Jon Emont. Shoe manufacturing relies on an army of skilled workers to perform fine manual labor, stitching and gluing a very wide variety of shoes together.

Ultimately, this effort was unsuccessful; Nike ended up closing the facility, and most shoes are still made by hand as of the writing of this article. And Nike isn’t the only example; small manufacturers in the United States rarely employ automation, far less than in near-peer countries like China or Germany.

There are a variety of reasons that automation seems to be taking off at different rates, ranging from technical to economic. Let’s go over some of the whys here: why automation is hard, where it fails, and why it seems to be moving faster in some areas than others.

If you like this blog, please consider subscribing, liking, or leaving a comment. Liking and subscribing helps others find these posts!

When Automation Works Well

Industrial automation actually works very well within its narrow operational constraints. So-called dark factories have existed since 2001, when FANUC began lights-out operations at its flagship facility, with robots producing other robots wholly in the dark for up to 30 days at a time, completely unmanned.

These dark factories have become an iconic feature of Chinese industry, with giants like Xiaomi and BYD increasingly employing them to mass-produce products like smartphones and cars.

But all of these products have something in common: with smartphones, or cars, or industrial robots, you might be building millions of units of product with very few variations. This justifies the larger up-front cost of traditional automation, which involves carefully designing assembly lines, planning robot placement, and even planning individual movements the robots will be making in perfect synchrony months ahead of time.

This is, to say the least, an incredibly expensive undertaking. It’s the work of systems integrators, companies that focus on building a particular class of robotics automation solutions. They will plan camera placements, write code, hook up sensors, design custom tools or parts — whatever is necessary to produce the perfect fully-autonomous production line.

Reasons People Skip Automation

Above: video of a small Chinese machine shop by Marco Castelli on X

Benjamin Gibbs of Ready Robotics wrote a thread on X a while ago, listing reasons why you don’t see more robots deployed, especially looking at small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs). In short:

Skepticism: the idea that many people know someone or have themselves tried to deploy a new industrial robot, and have not gotten a good return on their investment.

Opportunity cost: for a small, low-margin producer, spending $50,000 on a new robot makes a lot less sense than buying a new tool (also very expensive!) which can open up new revenue streams for the company

Software complexity: note that this is not the complexity of programming the robot, but of integrating various vision and safety systems, connecting to industrial PLCs, and so on. Each integration can be a massive undertaking with many different programming languages and (usually poorly documented) software packages involved.

Tooling design: industrial robots, as they are currently used in the United States, require very specialized end effectors to be useful. There is still no “universal” robot tooling; you cannot just order these parts off the shelf. Companies like Right Hand Robotics which once aimed to build more broadly-useful grippers and tools have always ended up narrowing their ambitions substantially.

Parts presentation: basically, the “art” of building a reliable input system for parts to arrive at the robot; almost every one of these has historically been custom-made and is therefore wildly expensive.

Electrical complexity: because there are so many custom parts and sensors, a shop looking to automate will need a custom electrical panel. They’ll need someone with wiring experience that they almost certainly lack in-house.

Let’s go back to the Nike example above. Their hope was that they could reproduce successes in building microprocessors, but applied to this new domain. Shoes are representative of a lot of the issues that robotics problems struggle with:

The wide variety of shoes produced, all with subtle differences, increases the human effort necessary to handle the full range of products during the process of automation systems integration

Similarly, the fact that shoes are made out of deformable materials means that the number of special parts and designs needed to fixture a shoe properly to grasp it 99.99% of the time and automate a full production line is extremely high

Safety sensors and integration requirements exist for partially automating production, which would not exist for a setup that’s not automated

Integrating all the specialized hardware used by a traditional systems integrator will be nearly impossible.

And the problem gets worse.

Automation in the United States

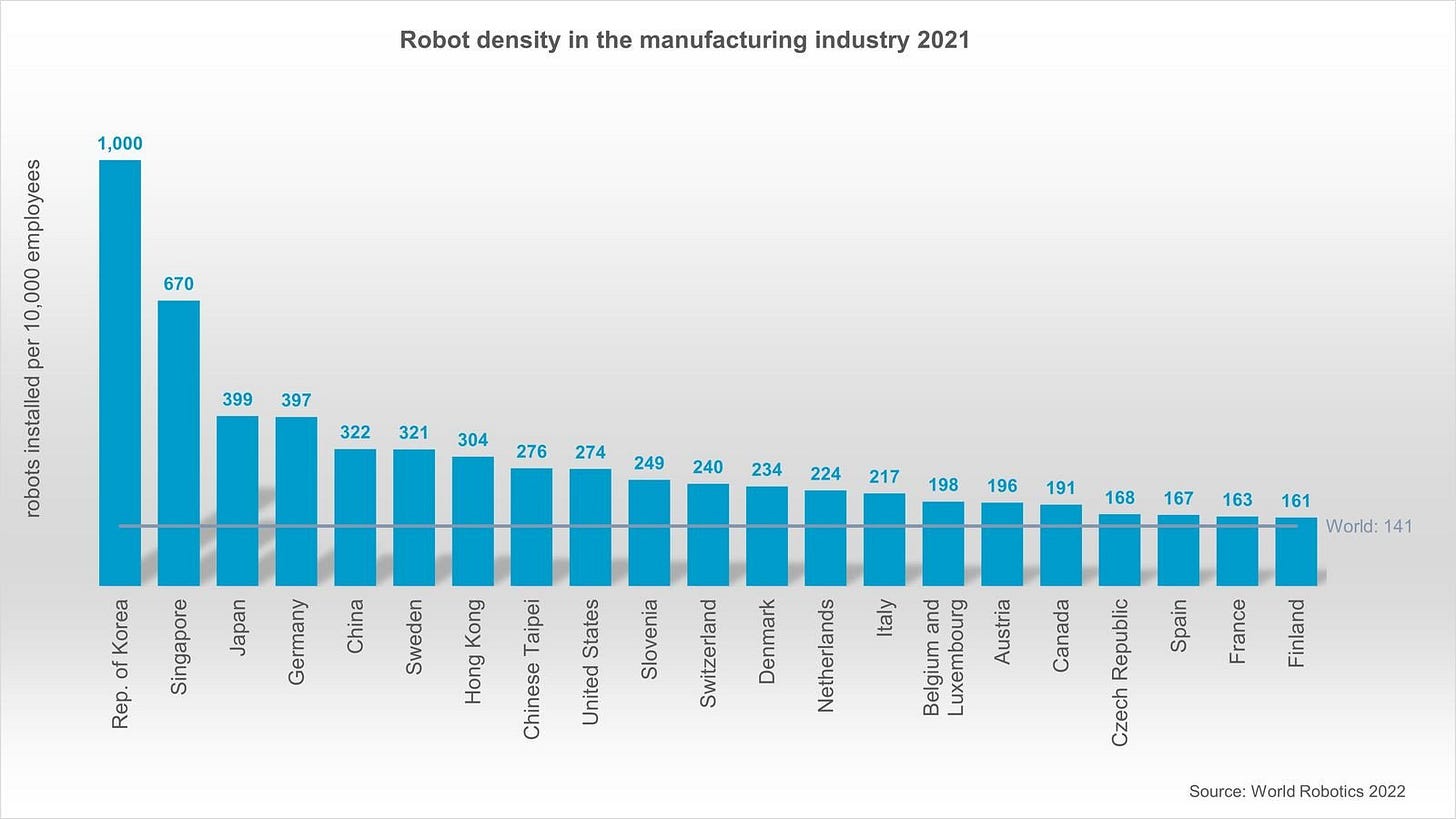

In 2021, China overtook the United States for number of robots deployed in manufacturing. By 2025, they’ve also overtaken anyone else, becoming the leading user of industrial robots in the world. This is not because of some technical edge — the bleeding edge of technology exemplified by companies like Physical Intelligence remains solidly American — but because of a complex ecosystem that enables production and deployment of robots economically and at scale.

As Andreesen-Horowitz noted in their report on robotics automation:

There are no “dark factories” in the United States. The closest that we have is Tesla’s Gigafactory Nevada, which is 90 percent automated. No other major manufacturer comes close.

Deployment costs and “cost disease” are endemic in many areas of American industry, and manufacturing appears to be no exception. As a result of these deployment hurdles, we often see that companies deploy robots only because they are forced to, usually by labor shortages.

It’s also noteworthy that, as mentioned above, current industrial automation requires a large number of custom parts, which means that the best returns will only appear at the very largest manufacturing scales. Without a robust ecosystem for custom systems integration work and a broad depth of expertise in the market, integration costs will remain extremely high.

So, in a way, it could be argued that we don’t use many robots, because costs are high, and costs are high because we don’t use many robots. This is a place where government action has worked in China, where there are often 10-20% up-front cash subsidies available for manufacturers. While the USA has similar incentives American subsidies take the form of tax breaks (such as Section 179(, which necessitate extra legal fees, overhead, and for the company to take that extra cost burden ahead of time anyway only to be “paid back” later. It’s perhaps a less efficient way for the government to spend the same amount of money.

The Future

In the end, we have two types of problems: shortcomings of current technology and shortcomings of the broader economy that make automation less tractable in the united states. Aggressive competition in manufacturing has led to better returns on scale, both internally to companies and to the country as a whole which benefits from robust supply chains, expertise, and labor markets.

But technology, here, might be a way out. The factory of the future probably does not use the wide range of specialized sensors and fixtures that Ben Gibbs mentioned in his thread. Modern vision-based AI systems are pretty good at handling deformable materials like clothes. Companies like Dyna and Physical Intelligence have shown dual-armed mobile platforms that are both reasonably affordable and capable of performing an extremely wide variety of useful tasks to a high degree of reliability, if not particularly quickly (yet).

The difference here is massive. These newer, lower-cost robots are safer to be around, they’re cheaper to replace, and they don’t need the massive diversity of custom sensors or fixtures to work properly. Instead, because they work by seeing the world like humans do, they can be placed in a production line more or less the way that humans are, with only a fairly labor-intensive bringup process to teach them a new skill. But note that this bringup process is still less labor intensive than the current arduous process undertaken by the systems integrators we discussed above!

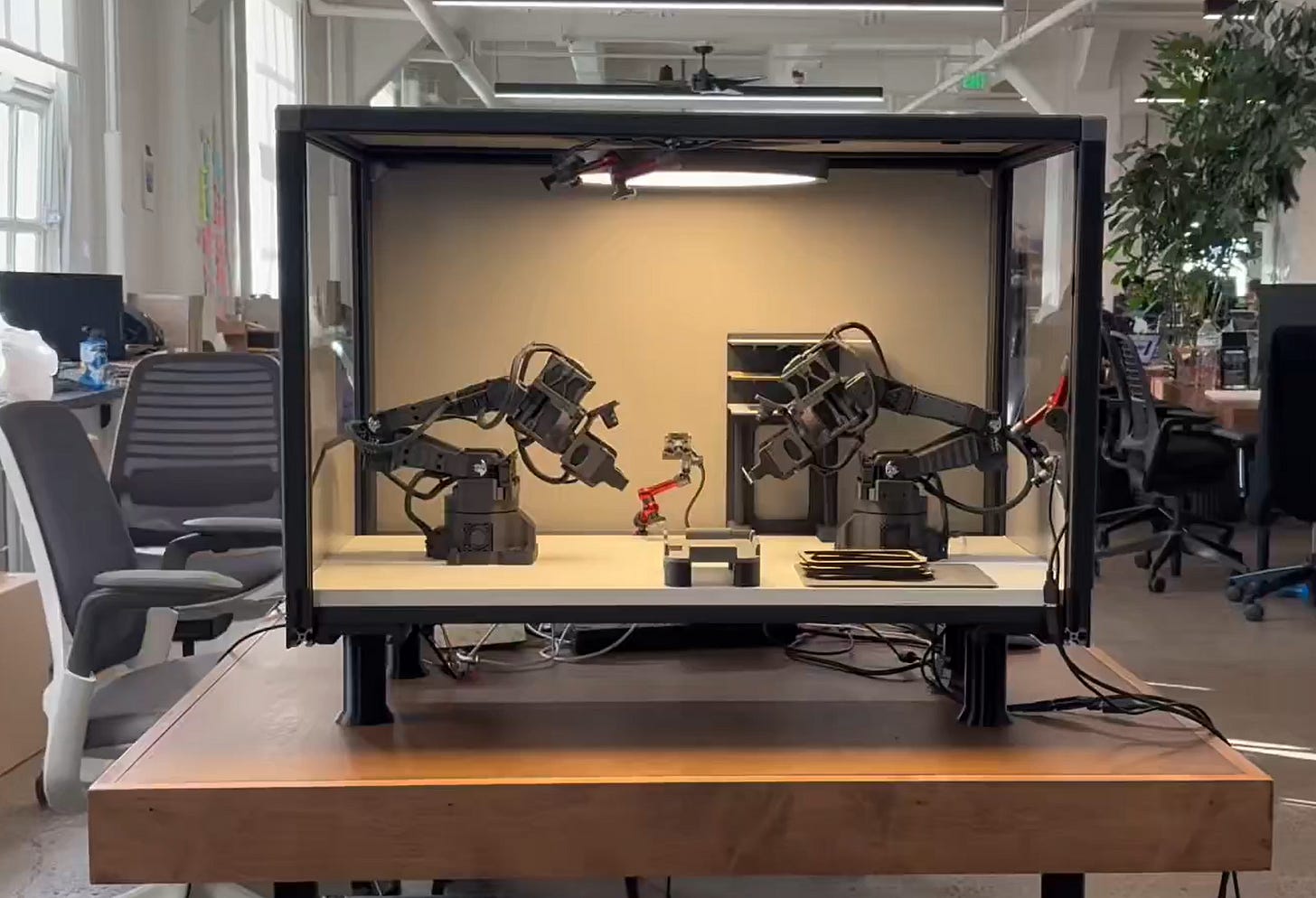

Perhaps in the farther future, we’ll see things like the MicroFactory take off: a bunch of cheap, modular robotic cells designed to be deployed in a controlled work cell, so that you could easily parallelize reinforcement learning training and deploy the robots at scale on a large production line. We’re already seeing companies like Standard Bots working to reinvent the formula.

Real technical challenges remain around speed, safety, and the general capability of these robots — as well as how to make their training more scalable and make the hardware more reliable. But the future of robotics manufacturing, it seems, will come from Silicon Valley and Austin, Texas, not the traditional manufacturing centers of the US, and it will be software-first.

If you liked this post, please like, share, and subscribe; or leave a comment with your thoughts below.

"Real technical challenges remain around speed, safety, and the general capability of these robots — as well as how to make their training more scalable and make the hardware more reliable. "

Great summary of it. Nicely written article thanks!

Nicely written! (As an engineer formerly employed in manufacturing automation)