How Human Should Your Humanoid Be?

A new version of the Boston Dynamics humanoid is coming and it looks even less human than the old one

Compared to other humanoid robots like Figure 03 or 1x NEO, Atlas is an alien. The product version of the storied humanoid robot from Boston Dynamics has strange-looking, bowed legs; it has an odd, circular head like a lamp, and all its joints can rotate all the way around.

If you want an illustration of just how strange this looks, watch this video from user CIX on X, recorded at CES 2026 in Las Vegas:

Contrast this with a humanoid like the Figure 03, which was clearly designed to mimic the appearance and capabilities of a biological human, something that I’ve covered before in a previous blog post.

Both of these robots are incredible pieces of hardware, but we must ask, why should Figure’s robot look so human while Boston Dynamics opts for such a strange form factor? Is it just a gimmick that Atlas can turn all the way around? If we’re moving away from the human form, why not just go all the way and make a robot that’s fully optimized for its task like the Dexterity Mech (video from Dexterity):

They do, on occasion, call this beast an “industrial superhumanoid,” and it’s a dedicated pick-and-place monster with a 60kg payload.

So let’s talk about why some of these robots look more or less human than others, and what the pluses and minuses are, with a particular focus on the new design from Boston Dynamics.

First, Why A Humanoid?

When asking why use a humanoid at all, the real question you’re asking is usually “why legs?” And this is an important question; lots of the robots, including the Dexterity Mech shown above, do not need legs. What are legs for, then?

Well, legs allow robots to:

Handle more complex and challenging terrain

Carry heavy things without requiring a large base

The first benefit is obvious — legs allow your robot to climb stairs or cross a debris-strewn landscape. They mean that your robot can be deployed in a wide variety of environments with far less concern about “preparing” the environment for robots.

This, however, rarely going to be a deal-breaker for real-world deployments, as it’s already economical to design industrial spaces to optimize productivity. Amazon, for instance, famously developed new techniques for creating flatter floors in its warehouses to benefit its Drive robots. So, in a real, large-scale deployment, legs are of use for handling terrain — but that’s only a very limited use.

More important is that legs allow robots to be smaller while performing the same tasks. Or, more accurately, it’s because a bipedal robot can perform the same work in a smaller, more constrained area. Because they’re dynamically stable and omnidirectional, an industrial humanoid robot like Atlas can carry a heavy load with a much smaller footprint than a robot like the Dexterity Mech.

This is important because in a factory or warehouse, you’re often trying to fit as much stuff into available space as possible — you don’t necessarily want all the extra space it needs to make a large, high-payload wheeled robot work.

But notably, this does not mean that your humanoid has to look human.

The New Atlas

The new Atlas robot has a couple unique design features, courtesy of product lead Mario Bollini on X:

And the unique legs:

With only two unique actuators, the supply chain and cost of the robot can be greatly reduced versus a more human-like design. The fact that the legs can bend forwards or backwards gives it some more flexibility, but also means that the legs are swappable left to right.

And with that in mind, let’s go back to that first video by CIX, where the (prototype, not mass production) Atlas reverses itself during a procedure. Remember when I said the main advantage of a humanoid was working in a more constrained space? This design grants the robot distinct advantages in constrained environments.

Why To Be Human

Contrast this with the approach taken by competing American humanoid manufacturers like Figure, 1X, or Tesla. Their robots are very closely designed to match the human form factor.

There are a few advantages to this:

Teleoperation is easier. Even if your robot is superhuman, the humans operating it are not — and teleoperation is already pretty hard work!

We have lots of human data already. The internet is filled with human video data; training from this data, as 1X has done, allows you to easily resolve the robot data gap.

Our tools and technologies are all designed to be used by humans. This is a favorite argument of Elon Musk, for example. If your robot is expected to use tools or drive a forklift, you might want it to look human.

It looks and acts human, and people like that. Robots that work around people need to be pleasant and likeable; people might not want to purchase these strange, scary alien beings whose heads can rotate 360 degrees.

There’s a safety angle to this final point as well; if a robot’s capabilities are roughly human, people know what to expect from it, and it’s important humans have a good model of what robots can do if they’re going to be working and living alongside them. This is a huge part of the justification for the design of the 1X NEO, which has very humanlike lifting strength and capabilities.

Personally, I find that there are a lot of holes in these arguments.

Robots Using Tools

I don’t buy that, in the future, we’ll want humanoid robots to use tools built for humans. When transportation in human cities switched from being dominated by horses to dominated by cars, every piece of our infrastructure changed. This will happen with robotics, too, as robots supplant human labor.

It seems very unlikely to me, for example, that humans will be buying non-robotic forklifts for their warehouses in 10 years. Every forklift will be something like a Third Wave robot; you certainly won’t be asking Optimus to go and drive a forklift, because the extra sensors necessary for automation will be extremely cheap.

The same will go for tools; maybe robots will have swappable end effectors, or maybe tools will be specifically designed with attachments for robot hands, but there’s no reason not to think that, at scale, you gain more from good, vertically-integrated design than from building something to support legacy hardware (humans) forever. Indeed, a modular robot like Atlas could eventually use these tools better than a human ever could.

At best, I think the robot tool use argument will be a short-term cost-saver that applies over the next couple years.

Is Data Collection Better With Humans?

This is a vastly better argument in favor of human mimicry, but the cracks are starting to show even here. Human teleoperation data, while essential for robot learning to this point, will not be able to take full advantage of superhuman humanoids.

But there are ways around this, and one is something we absolutely need no matter what: reinforcement learning. Says Atlas product lead Mario Bollini again:

Reinforcement learning is crucial for real-world reliability, as demonstrated in recent works like Probe-Learn-Distill from NVIDIA and RL-100 (both are RoboPapers podcast episodes you can watch/listen to). It also provides a way for us to start with human demonstrations but then improve upon them.

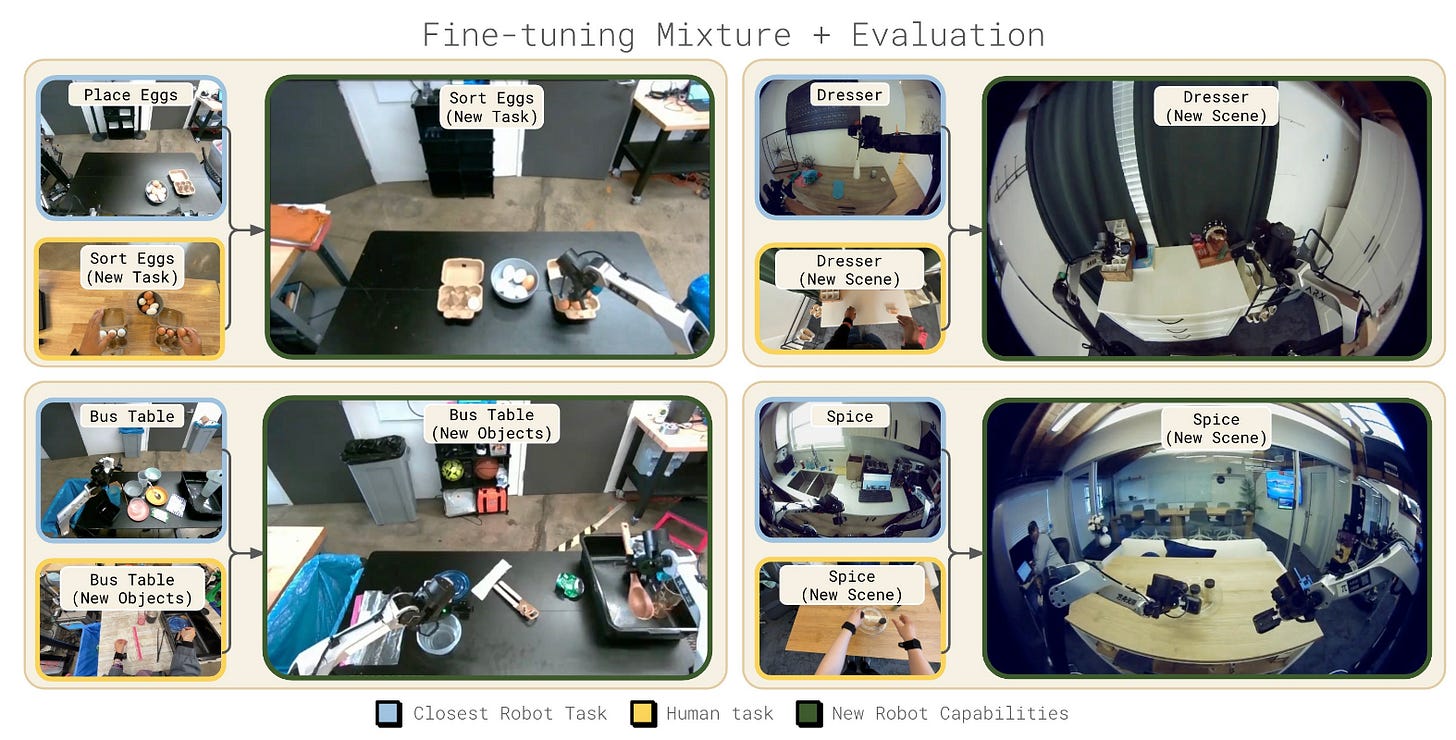

But what about human video data? Certainly, there’s compelling evidence that video data can improve performance with humanoid robots. I’ve discussed the importance of co-training on this blog before: how else could we ever we get enough data to train a Robot GPT?

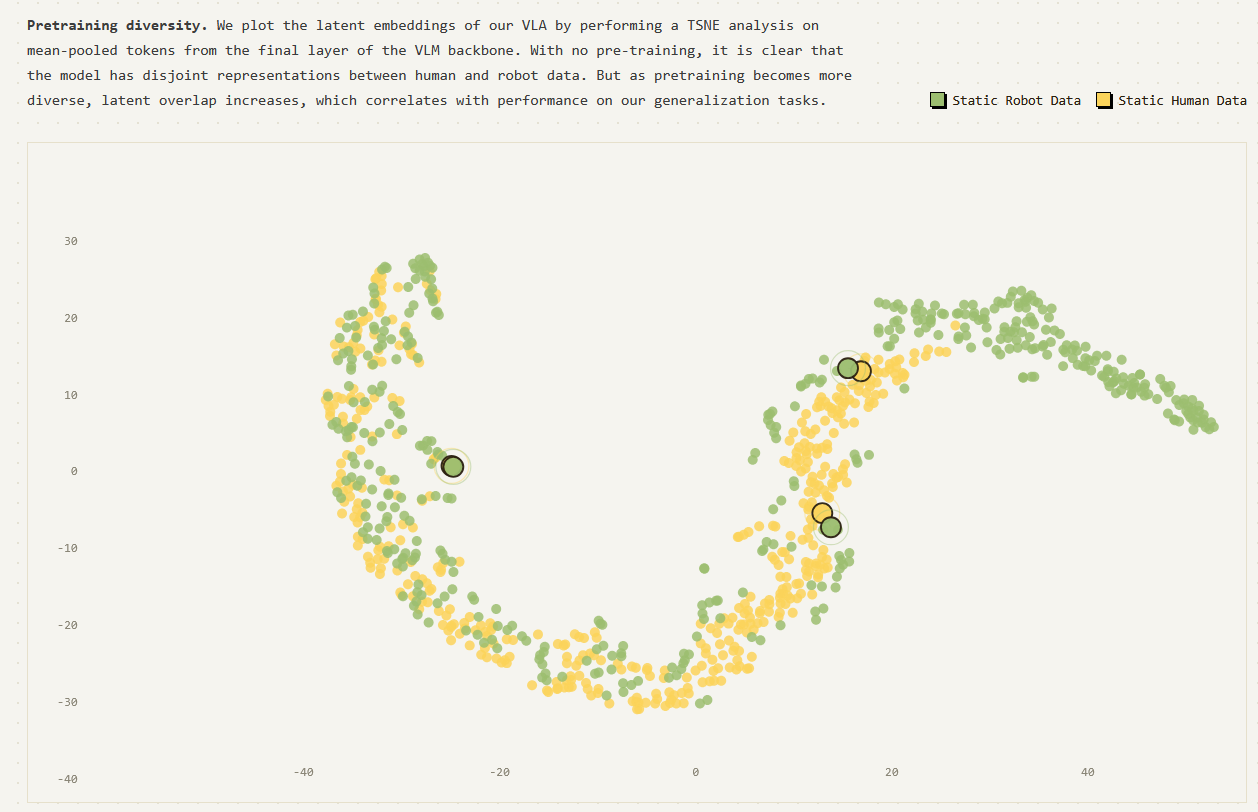

But your robot might not need to be human to take advantage of video data. Take a look at the the recent “Emergence of Human to Robot Transfer in VLAs,” by the Physical Intelligence team. In the plot above, the show how just by co-training on human and robot data, the models naturally learn a similar embedding space for tasks which is shared across the different embodiments.

And PI’s robots do not look remotely human! They’re very simple, lightweight research arms with two-finger grippers. Now, they’re not performing highly dexterous tasks in this case, and this might change, but I see no reason why as long as the robot hardware is capable of a task, that such a shared mapping cannot be learned.

As a final note: I don’t think there’s any particular reason human hands have five fingers. Dogs have five fingerbones, as do whales; neither of these animals use these at all. Humans have hands with five fingers by accident of evolution, nothing more — it is not the product of some optimal engineering process. And so I don’t see why our robots should be limited to that, either.

Final Thoughts

The humanoid form factor is, I think, here to stay due to its clear advantages, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that it will stay human. The Atlas is an interesting look at a very different vision of what a humanoid robot can and should be, and I think it’s exciting to see it come to fruition with a new model designed for mass production.

I also think there’s a huge opportunity here. As I mentioned above, one advantage of robots that look human is that you understand what humans can do. With a totally “alien” design like the new Atlas, the roboticists can rewrite the script: you know what a human can do, but also what Atlas can do. That kind of product identity will, I think, be very valuable as we approach a sort of “jagged” physical AGI in the coming decade or decades.

Please let me know your thoughts below, and share/like/subscribe to help others find this if you found it interesting.

Interesting post. Atlas could maybe be called a "post-humanoid" robot: a design that has evolved beyond straightforward imitation of the human form, while retaining the strengths of it.

A question about one aspect of post-humanoid robotic designs: sometimes we've seen robots that put wheels on their legs (instead of feet), so they can switch between walking and rolling depending on the situation. That seems to not be in favor recently, at least not with humanoids. Do you know why wheels-on-legs isn't popular?

Thanks, Chris, for the well-argued and written post, as usual. It well-articulated some of my developing thoughts from earlier this week on the implications of a human-demonstration-based pretraining architecture on the robot form itself. I think in addition to the limb morphology, there are similar implications on sensor layout for behaviors that need sensory feedback, such as sparse foothold mobility and tricky manipulation.