Are Humanoid Robots Ready for the Real World?

There are many good arguments why not to do this; but better reasons to move ahead

On October 28, 2025, for the first time, a humanoid robot designed to provide general-purpose assistance to humans went up for pre-order, from Norwegian-American startup 1x. Humanoid robotics company Figure recently announced its new, polished Figure 03, also designed for homes (which I wrote about here). Real, useful, capable home humanoid robots genuinely seem to be on the horizon: robots which might be able to load your dishes and fold your laundry.

And yet there’s still a substantial gap between the capabilities these companies are planning to show and what they’ve shown so far. This gap is widely acknowledged: Eric Jang of 1X posted a clear and heartfelt message on X, saying:

This is a product that is early for its time. Some features are still in active development & polish. There will be mistakes. We will quickly learn from them, and use your early feedback to improve NEO for broad adoption in every home.

Likewise, Brett Adcock of Figure argued at GTC that the primary challenge was solving general-purpose intelligence, not manufacturing.

And yet, people like robotics legend Rodney Brooks argue that today’s humanoids won’t be able to learn dexterous manipulation — that we’re far behind human capabilities and that this gap won’t be closed any time soon.

I think it’s worth taking a look at both sides, because while I’m very optimistic about useful home robots arriving in the next couple of years, I think there’s a lot of work to be done still.

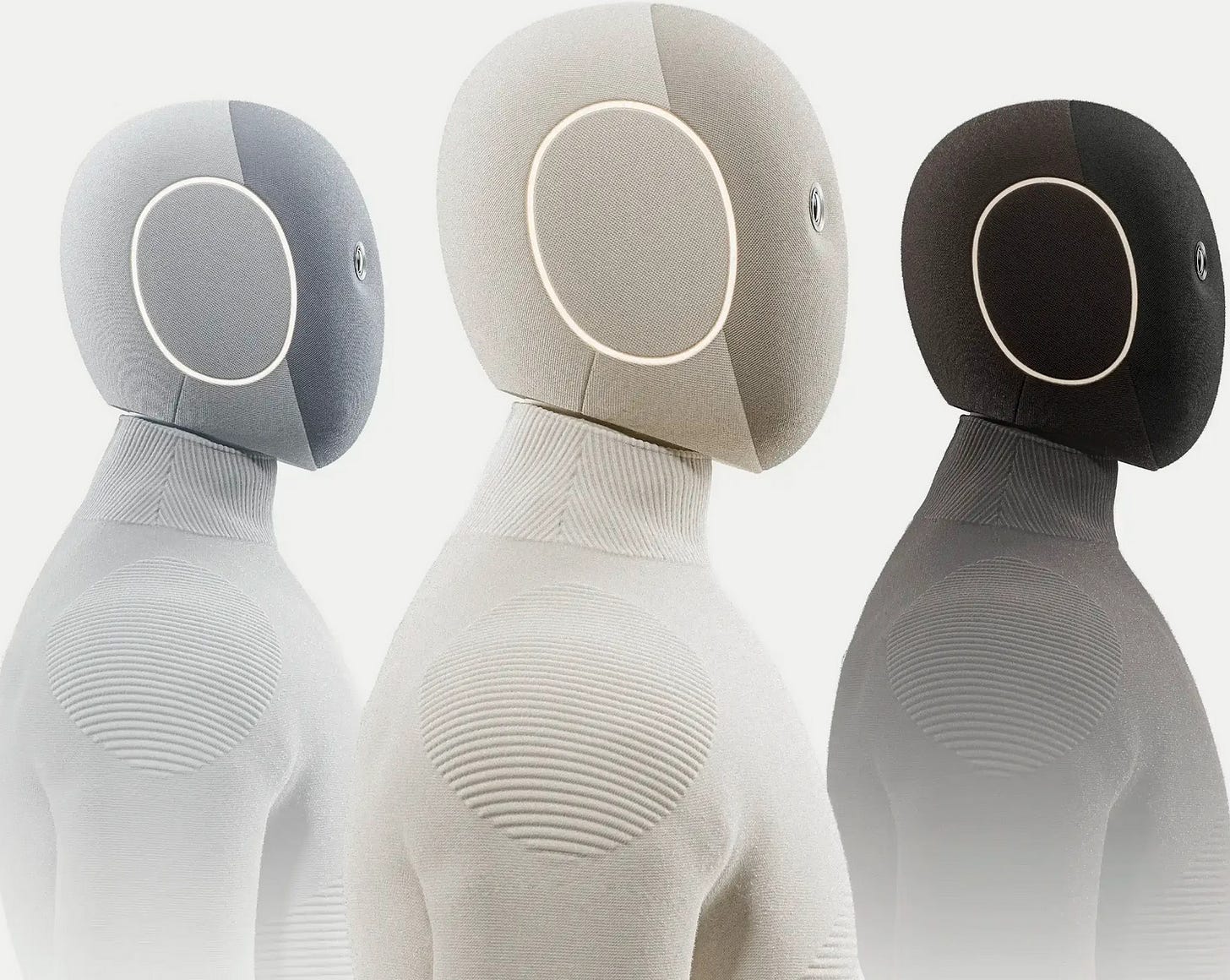

The First Home Humanoid

The 1X NEO launch was a real landmark in the field of robotics, and the robot has been impeccably designed for the home. It has a soft, friendly fabric covering; a semi-rigid, printed mesh exoskeleton instead of stainless steel, and a unique tendon-driven actuator system which delivers strength without excessive weight. All of this is designed around the idea that the 1X Neo will be the first safe, friendly, and capable robot that you can buy (for the incredibly low price of $20,000), and which will eventually help you do, well, just about anything.

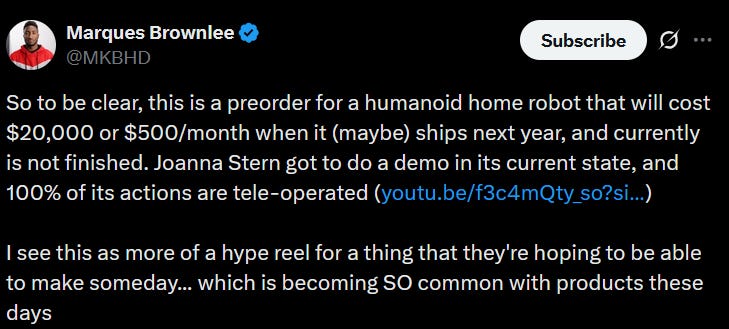

And yet! Not everyone is excited. Many feel betrayed, in fact, because large parts of the launch videos were teleoperated. Tech product reviewer Marques Brownlee posted this message in response to the 1X launch:

It’s also worth watching the video he mentions from Joanna Stern (on YouTube here). This is a very grounded and transparent look at NEO as it stands now, including a five-minute-long attempt to load a dishwasher with three items:

I’m the kind of person who thinks that robotics is a fundamentally exciting, transformative, and important technology for the future — as you can likely tell from the fact that I’m writing this blog in the first place. But if you were just looking for a robot that would do all your chores, some of this might be a bit disappointing: NEO will be slow, it will break, it will probably break your things once or twice. It will make mistakes, as Eric Jang said.

The idea is that by getting lots of robots out into homes, they’ll get diversity of data (crucial for scaling learning in robotics), and by having their own skilled teleoperators in the loop, they’ll also get high-quality data, which is likewise absolutely essential.

Fundamentally, this is a bet similar to one I’ve written about before: if we spend a bunch of money and deploy a whole lot of robots, we’ll get enough data — all the many billions of tokens — that will give us a GPT-like general model.

How can we get enough data to train a robot GPT?

It’s no secret that large language models are trained on massive amounts of data - many trillions of tokens. Even the largest robot datasets are quite far from this; in a year, Physical Intelligence collected about 10,000 hours worth of robot data to train their first foundation model, PI0.

In that previous blog, I’d claimed that it seemed about a $1 billion project to collect this amount of data in a year. Coincidentally, both Figure and 1X are looking at $1 billion dollars right now.

And, until then, we have teleoperators: experts employed by autonomy companies like 1X who will remotely operator your robot, figure out how to perform a task, and collect the demonstration data necessary to teach it to the robot.

There are real privacy concerns with this, but compared to the price and privacy risk of hiring a cleaning service, these seem minimal; if you’re paying $500 per month for a humanoid robot assistance, money was clearly not stopping you from getting your house cleaned regularly by a stranger.

The question, then, is: is all of this reasonable? Will this data actually give us a general purpose model that can perform useful manipulation tasks?

Reasons for Doubt

Robotics is hard, as roboticists are fond of reminding you. But with all the amazing progress we’ve seen over the last couple years, it can be easy to forget that there are actually a lot of things which remain very hard.

Robotics legend Rodney Brooks wrote a very widely-circulated blog post titled, “Why Today’s Humanoids Won’t Learn Dexterity.” And by widely-circulated I mean that at least a dozen people asked me if I agreed with it shortly after it went live (I don’t). But it’s still a great read, and raises a lot of important points that we should address.

First, Brooks discusses the “missing data” necessary to learn robot dexterity. This is not missing data in the sense of the millions of hours of robot teleop data people plan to collect; it’s missing data in the sense that it’s not being collected at all in many cases. Robots, he argues, need tactile and force sensing data to be truly reliable manipulators. Data at scale isn’t enough; it has to be the right data.

Second, he brings up the point that walking robots — at least full-sized humanoids — are broadly not very safe to be around. You may have seen this video which went viral of a robot freaking out; imagine the harm if that robot hit a child.

We see another serious concern raised by Khurram Javed in a recent blog post: the fact that it’s really hard to generalize to all of the incredibly diverse environments robots will inevitably encounter out-of-the-box, and is in fact probably impossible.

Every household has a set of dishes that are not dishwasher safe and must be hand-washed. This set differs from one household to another, and changes even in a single household over time. Learning to load a dishwasher successfully requires learning about the specific dishes in each household.

Finally, there’s one concern, which I think keeps me and many much more intelligent AI researchers up at night: what if learning from demonstration just doesn’t work? What if it can’t scale to the success rates and quality of performance we need?

Let’s address these one at a time, both in the context of 1X and other modern humanoid robots, and more generally.

1. Are Modern Robots Missing (Tactile) Data?

There are good reasons Rodney Brooks is making this argument.

Modern Vision-Language-Action models (VLAs) are actually quite bad at handling tasks which require even a very short memory. Usually, they’re going to work best when tasks are essentially Markov, so that from each frame you have all the information necessary to make the next decision.

This is a huge issue for grasping, specifically — especially for grasping unmodeled, previously-unseen objects. Tactile sensors make a lot of sense here; as the robot closes its grippers, the “sense of touch” in the robot’s hands kicks in, and it’s able to get a good, high-quality grasp with no danger of dropping the object.

Giving Robots a Sense of Touch

While we humans are, largely, visual creatures, we can’t solely rely on our eyes to perform tasks. This is a contrast to most modern robotics AI, for which the best practice i…

Where I think Brooks is wrong is that everyone knows this. The new Figure F03 has tactile sensors built into its hands. The 1X robot doesn’t appear to have actual tactile sensors, but you can get force/torque measurements from its tendons; these can be used to get a strong signal about grasping. A large part of NEO’s safety comes from its compliance, after all.

And it’s not just these two American humanoid companies, by the way — Chinese startup Sharpa recently showed their robot dealing blackjack at IROS 2025 in Hangzhou. This was teleoperated, but the robot does have tactile sensors, and is obviously capable of some impressive feats of dexterity!

Tactile data is somewhat unique in that it’s hard to get from teleop, largely because you can’t easily relay it back to the teleoperator. But the extra signal is still there, you’re just at the mercy of your demonstrations; perhaps this helps justify 1X’s broad rollout into homes.

Another trick we commonly see is the use of end effector cameras (present on the Figure 03). These can fulfill many of the same roles as the tactile sensors, while using a much more battle-tested sensing modality. They can let you reach into a cabinet where the robot's main cameras are occluded; they can detect deformation much more easily than head cameras can. In models trained using ALOHA arms, much of the “weight” a neural network puts on individual sensors comes from these end effector cameras instead of from any third-person view.

2. Are Walking Robots Dangerous?

Next, we have the argument that walking robots are dangerous: they have big, powerful motors, that can move quickly and cause serious harm.

I think personally this is a much stronger argument for avoiding humanoid robots in homes, but it’s one that everyone in the field has been thinking about carefully. In-home robots will be lighter weight — NEO for example is only 66 lbs. It also cannot exert the kind of sudden impulse that makes the Unitree G1 so dangerous when it goes wild, thanks to its tendon drives.

In-home humanoids will probably have to be lighter, and this may make them shorter. This makes the safety problems much more tractable. Robots like the Figure 03 are larger and might have a harder time, but Figure is also working on reducing mass, and covering the robot in soft cloth and foam.

Part of the safety, though, will have to come from intelligence, for any of these robots: being careful around stairs, learning how to fall safely if you absolutely must fall, having redundant, resilient electrical systems, compliant motion and enough camera coverage for adequate situational awareness.

Building safe robots for homes will be difficult, but I believe it will be possible.

3. Are Home Environments Too Diverse?

Obviously, every home is different from every other. More broadly, every environment will be at least somewhat different from every other. Worse, many of the tasks we care about are very complex: “put away the groceries” or “do the dishes”, which require many repeated contact-rich interactions with this previously-unseen world.

The solution to this will come in two phases. First, there will be an initial “exploration” phase for a new robot in a new home. Robots like the Amazon Astro or Matic (above) already have to deal with this; when you unpack a robot, it starts by exploring your home, building up a map. With Astro, you’ll also label rooms and viewpoints that the robot will care about. With humanoids, we should eventually expect something similar: a pre-mapping step where you show the robot all of the locations that it will need to deal with.

What’s different is that humanoid robots will also need to physically interact with the world. I share a lot of the concerns raised by skeptics that robots will be able to zero-shot perform useful tasks in a new home, but fortunately, they don’t need to. If a robot will struggle with something, you have two options:

Put on a Quest 3 headset and teach it yourself

Enable “Expert Mode” as 1x calls it; have a remote operator take over your robot and collect the handful of demonstrations you will need to adapt the robot to your environment.

I’m not sure whether 1x is planning to have a fine-tuned model for each robot (I would honestly expect so; at least at first!). In the end, the decision will be made empirically: they can do whatever works. The important part is that they have all of the tools available to do per-robot adaptation and to collect data to further improve their base model.

In the future, there are a lot of tools that I hope will make this easier; work like Instant Policy [1] looks at how we can set up in-context learning for robots, which is a way of adapting to new environments without training new models. The process of adapting to new environments will get substantially easier with more data; and the clearest route to getting the right data is to deploy robots at scale.

4. Is Learning from Demonstration Good Enough?

Finally, I raised the concern that maybe none of this will work. Perhaps performance gains from pure imitation learning will never achieve success rates that people are truly happy with in a consumer product.

This is a concern echoed by many people much smarter and more experienced with these methods than myself. Fortunately, that means all of these very smart people seem to be working on it.

The answer, at least in part, is reinforcement learning.

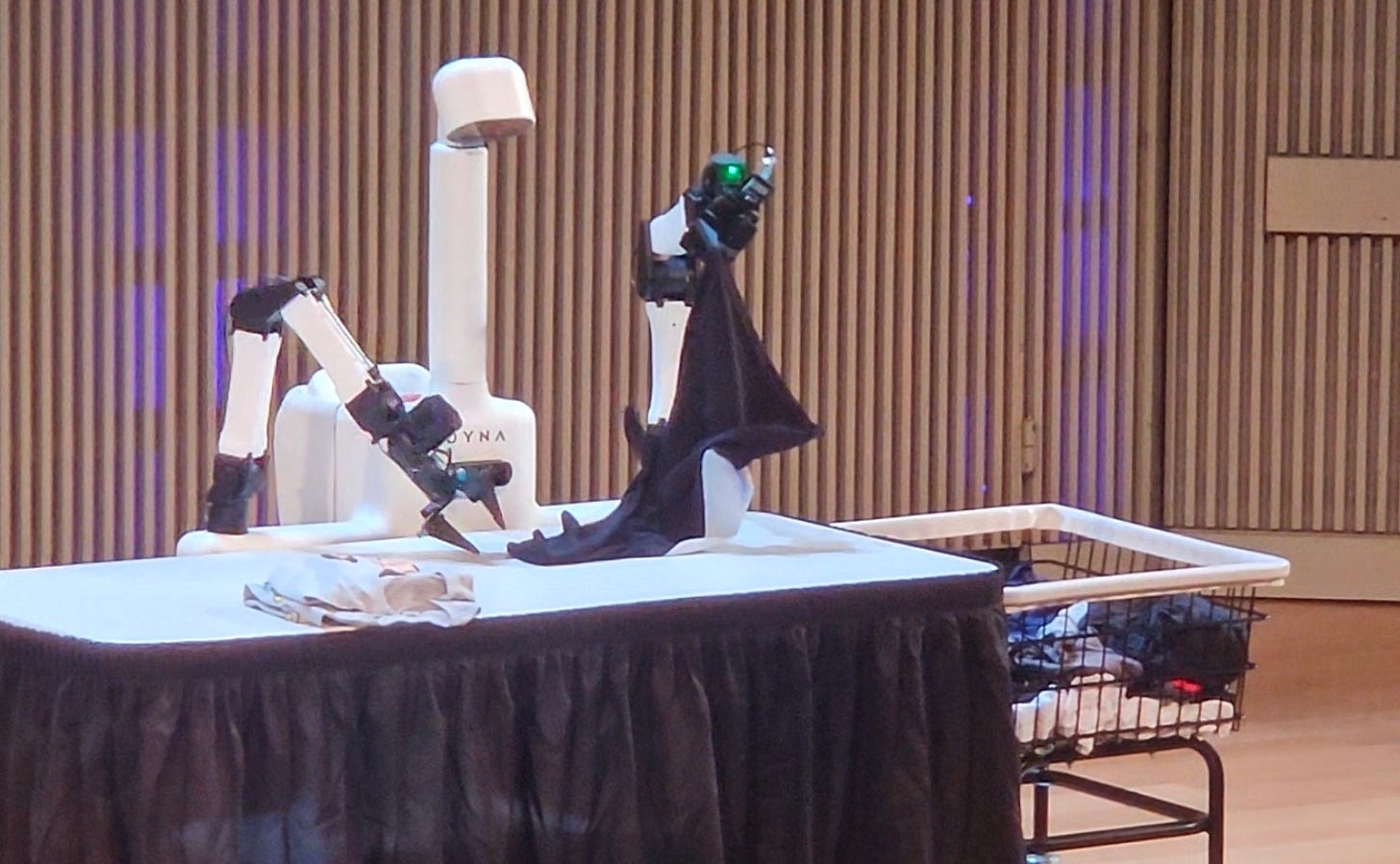

One of my favorite demos of the year, as I’ve written about before, was by Dyna Robotics, which shows their robot repeatedly folding t-shirts over and over again. They can run this demo now with such confidence that Dyna founder Jason Ma was able to give a talk onstage at Actuate while letting the policy run. And this was all zero-shot, meaning that the particular environment the robot was in had never been seen before — this constitutes a major achievement.

There’s been a line of recent research which has similarly achieved impressive results. Research papers like HiL-SERL [2], RL-100 [3], and Probe-Learn-Distill [4] all achieve up to 100% on various tasks over long time horizons using end-to-end visuomotor policies of various sorts.

It also seems likely that this will mesh well with the inclusion of tactile and force-torque data; while learning from demonstration is limited by the difficulty of providing tactile feedback to human experts, reinforcement learning suffers under no such limitations.

The Hard Things Remain Hard

I’m incredibly excited about the 1x NEO launch, and I am optimistic about the fact that it will succeed, given the time. It’s always worth keeping in mind the golden rule when watching robot videos:

The robot can do what you see it do, and literally nothing else.

Like, you see it loading a dishwasher — don’t assume it can load a different model dishwasher. You see it folding t-shirts, don’t assume it can fold a sweatshirt.

But increasingly, we’re seeing these robots out and about in the real world, doing a wide range of tasks. And while there are some rough spots still, all of the tools we need to get robots out into more environments clearly exist; we just need them them to be more refined. And the talented people at all these companies are doing just that.

References

[1] Vosylius, V., & Johns, E. (2024). Instant policy: In-context imitation learning via graph diffusion. arXiv preprint arXiv:2411.12633.

[2] Luo, J., Xu, C., Wu, J., & Levine, S. (2025). Precise and dexterous robotic manipulation via human-in-the-loop reinforcement learning. Science Robotics, 10(105), eads5033.

[3] Lei, K., Li, H., Yu, D., Wei, Z., Guo, L., Jiang, Z., ... & Xu, H. (2025). RL-100: Performant Robotic Manipulation with Real-World Reinforcement Learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2510.14830.

[4] Xiao, W., Lin, H., Peng, A., Xue, H., He, T., Xie, Y., et al. (2024). Self-improving vision-language-action models with data generation via residual RL. Paper link

I had the privilege of competing in the ANA Avatar XPRIZE four years ago, and as you know, the core challenge was teleoperation. Beyond the invaluable lessons we learned — such as the fact that the technology must ultimately outperform the mediocre human teleoperator — the challenges have only grown: if you commit to logging outgoing commands, you must also log the return signals and the surrounding perception data.

Transfer learning is the only viable path forward, and this is where not only open source becomes essential: an open telerobotics experience is an absolute must.

TeleHug from México 🥳🥳🥳

Insightful. Given the clear divide between ambitious goals and current dexterous manipulation capabilities, where do you see the primary bottleneck: fundamental AI algorythms or more robust hardware-software integration? Your balanced perspective, acknowledging both the optimism for useful home robots and the significant work ahead, is truly refreshing and well-articulated.